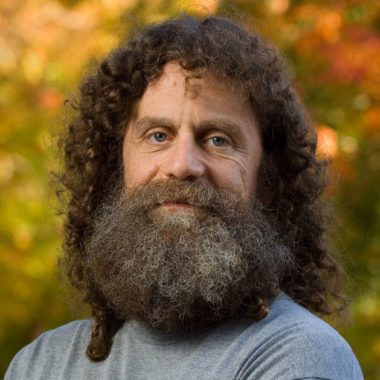

Dacher Keltner: Well, what a delight and congratulations on Behave. It’s a tour de force and a brilliant examination of the human being.

Dacher Keltner: Well, what a delight and congratulations on Behave. It’s a tour de force and a brilliant examination of the human being.

Robert Sapolsky: Mostly delighted not to have to be writing it anymore.

Dacher Keltner: Took a while?

Robert Sapolsky: Yes.

Dacher Keltner: So I wanted to ask you about your childhood because I’m a psychologist, so…

Robert Sapolsky: Okay.

Dacher Keltner: And I know early in your life growing up you started writing primatologists. And I want to ask you about that as a kid. But what was your first experience with science? When did you start to think that I have a scientific imagination and this is what I’m going to do in the world?

Robert Sapolsky: Well, I think I spent about four or five years, roughly ages three to eight or so thinking I wanted to grow up and be a chimpanzee. Um, and I eventually…

Dacher Keltner: You’re doing pretty well at that one, I bet.

Robert Sapolsky: Well, it depends what parasites you have. And then, you know, all of us have to grow up at some point. And I had to sort of come to terms with the fact that I couldn’t be a chimp. And it struck me that just scientifically one’s fallback would be to go study them. And thus was born a primatology interest.

Dacher Keltner: So you wrote primatologists as a kid?

Robert Sapolsky: When I was about 12, I was sending fan letters to various primatologists. I still meet some of these guys, these emeritus guys, who dimly remember these crayon sort of fan letter things. So yeah, that was my substitute for an interest in sports or something like that.

Dacher Keltner: Yeah. Most of us are writing baseball heroes, and you’re writing, you know, Jane Goodall. That’s that’s spectacular. So I’ve had some people come from your lab to my lab over in Berkeley, very grateful for the training that you provide. And it’s an unusual place. It has a piano. And what do you do with, what’s a piano doing in your lab?

Robert Sapolsky: Well, that’s what my first paycheck went for as an assistant professor. I dunno, years before there was this guy, Thomas Eisner, who is like this god of entomology at Cornell who I sort of thought was god-like apparently. And I just thought it was so cool. I was, at one point, a serious pianist, and he apparently spent years as the conductor of the Ithaca Symphony when he was not doing phenomenal research. So just hearing he had a piano, well, I decided I needed to do that as well.

And that definitely got me some amazing pianists in my lab over the years, which mostly intimidated me out of ever playing the piano in the lab. So it was very counterproductive.

Dacher Keltner: So you’ve helped with show tunes with your kids at school and helped with their theater program…

Robert Sapolsky: Exactly.

Dacher Keltner: So you’ve studied molecules and you’re interested in cortisol and we’ll talk about the stress hormone cortisol a little bit later. But then you packed your bags in the summer and you’d go off to Kenya and you observed one group of baboons over there. How long did you spend observing these baboons?

Robert Sapolsky: Thirty-three summers? Thirty-two summers.

Dacher Keltner: Nice way to relax, ya?

Robert Sapolsky: Yes, exactly.

Dacher Keltner: What was that like? I mean, tell me, what are some of the central insights?

Robert Sapolsky: Well, I pretty much camped under the same tree for about twenty-five years, which suggests not a whole lot of imagination, but it was a nice tree. But in terms of the baboons, basically what I was interested in was stress and health and essentially… if you’re a baboon, what does your social rank, what does your personality, what does the culture of your troop have to do with who’s got the rotten cholesterol levels? Who’s got the elevated blood pressure, reproductive irregularities, all of that. So when I was twenty starting out there, it was absolutely clear to me what it was all about, which was it’s all your dominance rank.

And if you’re going to be a male baboon, and you’ve got a choice in the matter, you want to be a high ranking male. And in a very rough sense, yeah, it kind of looks like that in terms of health and stress-related disease and stuff. And it took me about twenty years to start getting enough insight and, I suspect, maturation to realize that much, much more interesting was to look at the personalities of these guys. Because it turns out you could be the highest ranking baboon in the continent, and if you’ve got this hyperreactive, anxious, neurotic personality, your physiology is going to be just as awful as if you were low ranking. And it took me even longer to realize that basically, if you’ve got a choice between being a high ranking baboon or one with a lot of grooming partners, the latter is much better for your health. Which could not remotely have seemed plausible to me when I was twenty.

Dacher Keltner: But encouraging and hopeful for your good prospects in life.

Robert Sapolsky: Yes, exactly.

Dacher Keltner: How many hours a day would you watch the baboons?

Robert Sapolsky: About eleven.

Dacher Keltner: God…

Robert Sapolsky: You know you sort of get up at… what else is there to do? It’s, like, no TV. It’s, like, the mail never comes. No, you go out. You know, you essentially just sort of hang out with them all day and keep track of who’s doing what. And then with some regularity I would dart, and that’s them using a blow gun system, which is at least as fun as it sounds. Which was, christ, you can be a bleeding heart liberal and you crawl around and get to shoot baboons in the ass with a dart. It’s fabulous. I loved it. I had no interest in the science, it was just for doing the darting.

Dacher Keltner: Finally you get your revenge on those middle school of baboons.

Robert Sapolsky: Yes. Took long enough.

Dacher Keltner: Now we’re getting to the deeper motives of Robert Sapolsky.

Robert Sapolsky: Not fear, psychologist.

Dacher Keltner: Excellent. I want to return to your thinking about dominance and rank in just a bit. Because Robert, early in the mid- and late eighties starts to make these claims about what it means to be low-ranked that really shape our study of social class, which we’ll get to in just a second. So let’s talk about Behave, and the spectacular tour that you take on, really, all different levels of analysis. Of thinking about why we behave as we do, and the good and the bad and human behavior. And I want to talk about brains, hormones, genes, and experience. And then we’ll step back a little and take on some deep philosophical questions. So one thing we’ve learned, and I just want to get your impressions on that and what you think the key insights are, is that a lot of people have speculated about the unconscious, gut feelings, psychologists like to call it automatic processes. And you tour a couple of interesting brain structures, the amygdala, and then the mesolimbic area or the ventral striatum and the dopamine circuits. And we get a lot of clues about what these structures do for us from people like Ulrike Meinhof, the terrorist. So what’s that story?

Robert Sapolsky: Okay. Amygdala is all about aggression, until you look more closely. And then you see it’s actually all about fear and anxiety, which thus tells you an awful lot about aggression. In a world in which no amygdaloid neurons need be afraid, we’d all be sleeping between lions and lambs. Just the extent to which aggression is anchored in fear and provocation and threat and ambiguity.

So the evidence for that has been all the usual lab techniques. You stimulate it in an animal, you get an aggressive outburst. You lesion it, you don’t see any aggression anymore. But bizarrely there’s been a few rare human cases of people with tumors in their amygdala associated with outbursts of violence. The first one in a sort of a literature is someone who has defined one of the cliches of contemporary violence, the guy Charles Whitman. This is like a trivia question on Jeopardy for $2,000. Charles Whitman is the guy in the early sixties who climbed the tower at University of Texas and opened fire on everyone below. This was literally the first choir boy from next door. The guy was an Eagle scout. Then what was that about? He had spent the previous year searching out doctors saying, ‘I don’t know why I’m having these violent thoughts, but they’re making no sense to me. But I’m having these horrible, violent thoughts.’ And on post-mortem had a tumor in his amygdala.

Another individual, as you mentioned… oh, what was their formal name, the gang? They had some Trotskyites sort of name, but the Baader-Meinhof gang, one of the extreme leftist, radical groups in West Germany in the eighties or something, she, one of the two leaders, had been a totally conventional, genteelly, left-leaning journalist before she suddenly veered into great violence. And post-mortem tumor in the amygdala. You know, some odd biology happening there.

Dacher Keltner: Absolutely. Tell us about dopamine. I love how you grapple with something that perhaps a lot of people in the audience are grappling with, which is, you have these mysterious primates in your house called teenagers. Then you consult, being who you are, you consult the neuroscience and it helps you understand teenagers. So what does dopamine tell us about pleasure and happiness and teenage life?

Robert Sapolsky: Well, it doesn’t make me any more effective at the parenting aspects, but, dopamine. Okay. Everybody knows what dopamine is about. It’s about pleasure. Cocaine works on dopamine, synapses, all the euphoriants do, it’s about pleasure. It’s about reward. It’s about that buzz after it happens. Until you look closely. And it’s not about that at all. It’s about the anticipation. That’s where you get the biggest draws in dopamine. The anticipation beforehand. And in addition, it’s the thing that drives the behavior you need to do to get that reward. That’s where the motivation comes from. That’s where the goal-seeking behavior comes from. And what’s totally fascinating is when you get somebody on an intermittent reinforcement schedule, as opposed to you do the work, you get to reward, you do the work, you get a reward, now it’s that you do the work, you get a reward about 50% of the time and dopamine goes through the roof. Like nothing you will see in a mammal. What have you done? You have stuck into the equation the word ‘maybe.’ ‘Maybe’ is unbelievably addictive. ‘Maybe’ just pours dopamine out of there. ‘Maybe’ gets you studying for good SAT scores to get into a good college, to get a good job, to get into a good nursing home. And it’s just like this whole cascade of expectation.

Dacher Keltner: Is this what you teach your children?

Robert Sapolsky: God, no wonder they don’t want to hang around.

Dacher Keltner: Is that the philosophy of life? The delight of ‘maybe?’ Is nirvana ‘maybe?’

Robert Sapolsky: Well, it is because we’re teetering right on this fulcrum there. If you’re sitting there saying, ‘God, I’m such a schmuck, but oh, today’s my lucky day, but this time it’s going to work, and I have my lucky socks on, but no, cause I always mess up.’ And just teetering there… The most brilliant dopamine sort of psychobiologists on Earth, namely the people who run Las Vegas, completely understand this principle. Their job is to take a circumstance where you have one in 10,000 chance of it working out well and convincing you that you, and especially you today, because of all these special circumstances, we’re going to manipulate you into believing that you have like virtual 50% certainty. And you’re just like, dopamine dribbling out of your ears at that point. So the thing about teenagers, is…

Dacher Keltner: And you wrote this while you had a couple of teenagers in the house.

Robert Sapolsky: Yes, indeed. And they were wonderful test subjects. The thing about teenagers is the dopamine system works absolutely full blast. You are already at basically adult levels by the time you’re twelve or thirteen. Most of the brain is going full blast at that point. The one area of the brain that is not is probably the most interesting part of the brain which is the frontal cortex. Frontal cortex is the most recently evolved part of the brain. We’ve got more of it or more complex frontal cortex than any other species out there. What does the frontal cortex do? It makes you do the harder thing when it’s the right thing to do. Gratification, postponement, long-term planning, executive function, impulse control, emotional regulation.

And the thing is, in teenagers, the frontal cortex is still kind of half-baked. It’s the last part of the brain to fully mature. It is not wired up until you’re about 25 years old, which says a huge amount about freshman year in college or things like that. So you’ve got this dopamine system that’s going full blast and what the frontal cortex normally does is a whole lot of just steadying hand put in there. And thus you’ve got a gyroscope where the highs are higher and the lows are lower and that’s an adolescent…

Dacher Keltner: It’s a pretty picture.

Robert Sapolsky: Yes.

Dacher Keltner: So let’s talk about hormones, our second causal force in human behavior. You’ve done a lot of work on cortisol and the stress hormone. Why zebras don’t get ulcers, which is really about how toxic it is when we have chronically elevated levels of cortisol. But we always get testosterone wrong, don’t we? Now why is that?

Robert Sapolsky: Testosterone has gotten this awful rap. Where, as we’ll see, oxytocin has had this Teflon presidency, that’s totally undeserved. Testosterone, what does everybody know about testosterone? Testosterone is the reason why world over, regardless of the species, regardless of the culture, that’s why males are such a pain in the rear. Because testosterone causes aggression.

Dacher Keltner: Now let’s hold off on this. Let’s pause here.

Robert Sapolsky: Okay. It’s going to get complicated. So testosterone causes aggression until you look more closely. What testosterone mostly does is it makes you more sensitive to whatever environmental cues trigger aggression in you. Like classic example: take five male Rhesus monkeys and they form the dominance hierarchy. Number one dominates two through five, number two dominates three through five, so on. Take the guy in the middle and inject him with testosterone, like enough testosterone to grow antlers on every neuron in his brain. Tons of testosterone. So does number three now turn into this raging son of a bitch who takes on numbers two and one? Never. All that happens is he becomes a total nightmare to numbers four and five. Testosterone does not invent new pathways of aggression. It increases the volume of the pathways that are already there from social learning.

So it’s not causing aggression, but then comes even a better wrinkle in the testosterone story. Which is this idea that came through about fifteen years ago that what testosterone is mostly good for is it makes you do whatever behavior is needed to hold on to status when it’s being challenged.

So if you’re a baboon, it’s obvious what you do that’s aggression. That’s synonymous with it. But with humans…

Dacher Keltner: You Tweet at three in the morning….or you have weird blonde hair.

Robert Sapolsky: I think the problem with testosterone there probably goes in the opposite direction. I think we’re seeing something compensatory. But with humans, if you set up a situation in which you gain status by, for example, being generous, testosterone makes people more generous. Which is like, if you took a thousand Buddhist monks and shot them up with testosterone, they would just run through the streets, doing random acts of kindness and seeing like you could do the most of them the fastest.

Dacher Keltner: Let’s write the grant.

Robert Sapolsky: Exactly, exactly. So the problem isn’t that testosterone causes aggression. The problem is we hand out status for aggression so readily. That’s where the problem is.

Dacher Keltner: So you broke my heart with the review on oxytocin. So tell me why I’m wrong. If I built an oxytocin bomb and I dropped it on the Capitol, why would we not have world peace?

Because as the audience knows, oxytocin is involved in milk let down and breastfeeding and oceanic feelings of cooperations…

Robert Sapolsky: Mother-infant bonding, and monogamous pair bonding. And you give oxytocin to rats and they’re better listeners to your problems. Like fruit flies sing like Joan Baez when you give them oxytocin.

It’s this amazing, wondrous pro-social hormone.

Dacher Keltner: Is that a finding, the fruit fly finding?

Robert Sapolsky: Yes. Yes. It hasn’t been replicated.

And that’s exactly how it works until….you look more closely. This has been some totally cool work that’s come out of the Netherlands showing that oxytocin makes you much nicer and more empathic and more expressive and all of that stuff to people who you feel are just like you, to in-group members. When it comes to out-group members, it makes you crappier to them, more preemptively aggressive, less cooperative.

Dacher Keltner: People are groaning out there. You’re breaking some hearts.

Robert Sapolsky: I know. It’s all the people who invested in all those oxytocin companies that could sort of spray out there. This one fabulous study, and this was the Dutch group that pioneered this, they gave a bunch of subjects this classic problem and philosophy of the runaway trolley. Is it okay to sacrifice one person pushing them on the tracks in order to save five? You know, psychologists have been making a living with that one for thousands of years with runaway trolleys. So they’re doing that with these volunteers and they do something, which is they give the person you’re contemplating pushing onto the track or not a name.

A third of the time they give them, what’s apparently just some classic Dutch name, like Dirk or something like that. And the rest of the time they tap into the two sort of negative national stereotypes that people in the Netherlands have. One is against Germans. Oh yeah. World War II. That’s right. And the other is against people from Islamic backgrounds. So now you’re having a choice: Do you push Dirk onto the track? Do you push Wolfgang onto the track? Do you push Mahmoud onto the track? And giving them the names has no effect on people’s decisions, but you give them oxytocin and suddenly you’re real resistant to pushing good old Dirk onto the tracks and, you know, Otto and Ahmed, you can’t throw onto the trolley fast enough.

It turns out oxytocin makes us nicer to people like us. It makes us more xenophobic to them.

Dacher Keltner: Biology’s a little complicated.

Robert Sapolsky: It’s a little complicated. And for my money, there’s no effect out there that could go here’s a hormone that makes you like broccoli more, but cauliflower less. It tells you this us-them divide, that’s a major fault line in the brain if you get a hormone doing diametrically opposite things to those two classes of people.

Dacher Keltner: Absolutely. I’m going to return to the us-them towards the end of our time together. So let’s talk about genes and deep life experiences. Our third causal process that’s producing behavior. This is the historical dimension to what causes us to behave as we do. You know, ten, fifteen years ago, there was so much excitement about genes and popular books came out that there were genes for cooperation and empathy, and we’ve actually done a little bit of work on that and aggression and depression. How’s that promise of the genetic enterprise fared?

Robert Sapolsky: Well, depends how over the top enthusiastic he were at the time. You know, there was that period where DNA was the code of codes and the Holy Grail and all of that. And basically genes have no idea what they’re doing. They have no more idea what they’re doing than does the recipe on a chocolate cake box at the market. It’s simply the recipe. It’s simply the readout. It’s whoever decides to read it out, whatever’s regulating the genes. And what’s regulating the genes is environment. Environment writ small inside a cell, the cellular environment is running out of energy. There’s a sensor which gets activated when there’s not a whole lot of glucose in the cell. It goes to the DNA and it turns on a gene that makes a thing called a glucose transporter, and the cell takes up more energy. Or environment in the whole body sense — you’re a wildebeast, it’s that time of year and you’re secreting testosterone. And as a result, testosterone goes to muscle cells, and it binds a receptor, which goes to the DNA and turns on genes that make the cell get bigger. You put on muscle mass. Then its environment in the everyday sense — you’re a mother of a newborn and you smell your baby’s rear end. And as a result of just the right combination of pheromones, you activate genes having to do with oxytocin.

Like ‘Ooh, code of codes, smelling your baby’s tush is regulating your genes.’ Genes don’t know what they’re doing. They’re regulated by environment and probably the most important thing about that is genes work differently in different environments.

Dacher Keltner: Yeah. Very important lesson. So now let’s take a step back and I want to ask you a couple of more philosophical questions. The literature that you just described, and when you think about the study of epigenetics and the environmental factors that make one gene predispose you to aggression, same gene without physical abuse early does not lead to aggression, same kind of findings for depression, with Avshalom Caspi and his colleagues. How malleable do you think we are? I mean, it’s almost as if you’re making this broad, bold argument away from modularity in the brain and genetic determinism and all those processes, too. If smelling a baby’s tush — or do you say tushy? I’m sorry, I didn’t get the term right —

Robert Sapolsky: It depends on which group study. The terms vary. Jargon.

Dacher Keltner: Okay. I mean, how big are the effects of these transient experiences on our nervous system?

Robert Sapolsky: They’re incredibly powerful. I mean you mentioned low glucose or testosterone or a certain smell when you turn genes on and off, you mentioned epigenetics, which is this process by which you could turn genes on or off in particular parts of the body for your entire lifetime.

So much of epigenetic effects are occurring when you’re a fetus, when you’re an infant, when you’re developing. That’s where, for example, prenatal exposure to lots of stress hormones from your mother and as a result of epigenetics, your amygdala is going to be bigger when you’re an adult, and more reactive to threat and provocation.

The thing that is most stupefying about that literature is one additional step. And this is work that was pioneered by this guy Michael Meaney who’s an old friend and colleague at McGill University. Turns out there’s good rat mothers and bad rat mothers and they differ in their mothering styles. What does a good rat mother do? She licks her pups a lot. She grooms them. She carries them around. Bad rat mothers, I dunno, just text the whole time or something… Yes, I have a teenage daughter. So one of the first things they showed was if you have a good attentive rat mother, when you are a rat pup, as a result, that will cause epigenetic changes in this one part of the brain called the hippocampus. And as an adult, you will have lower levels of stress hormones. Totally cool. They show that effects the old age in these rats, likelihood of memory loss and old age. Wow, lifelong. But then an additional thing which is if you had one of those wonderful attentive moms, and as a result of those epigenetic changes as an adult you have less lower stress hormone levels, you’re more likely to be one of those attentive moms. And thus you pass on the traits, multi-generationally.

Dacher Keltner: Incredible.

Robert Sapolsky: Phenomenal. And that one is non-genetic. That’s non-genetic transmission of a trait. So some of these early effects are phenomenally long-lasting and they’re all built around, not what sequence of genes you have, but how readily you regulate certain genes, which is a world of difference.

Dacher Keltner: Yeah, it is. You grapple with freewill. I’m not sure if you take on consciousness in the book or where kind of choice and intentionality is in the mind. With this big cocktail that we’ve talked about with brains and hormones and genes and experiences, where is thought and freewill in this?

Robert Sapolsky: Oh, you know…

Dacher Keltner: Or should we even ask the question?

Robert Sapolsky: Well, the, the nice conciliatory thing I used to say is, well, if there’s free will, it’s getting in all these really boring places. You want to claim freewill is that you brushed your top teeth before your bottom ones today instead of the usual the other way around, but it’s just getting crammed into tighter and tighter spaces.

I think it’s essentially impossible to do a survey of all of the things regulating behavior, from what’s going on in your brain one second before to all of the sensory stimuli in the world around you that you haven’t the remotest idea are pertinent, to the nutritional environment you had as a fetus, to whether your ancestors constructed a culture of honor or a culture of cooperativity, to how your species evolved. I think it’s basically impossible to see the full span of these and think there’s the slightest room in there for free will. Free will is the term we give to the biology we haven’t discovered yet.

Dacher Keltner: You’ve got a philosophical movement. You should run for president. Alright, so let’s shift gears a little. I want to talk about your deep reflections on the complicated primate that we are. You know, it’s so refreshing in Behave because when we speculate about our deep origins and the deep design of who we are, we find our favorite primate relative and we become convinced we’re bonobos, matrilineal, having sex all the time, living in Haight Ashbury, or whatever it is. You know, we think about hunter-gatherers and we try to infer their laws to our own… and you take a more complicated view of who we are.

So the first thing that really jumps out is we’re a hierarchical species. So what, what do you think about human hierarchies? How are they different from the baboon hierarchies that you observed for thirty years?

Robert Sapolsky: Well, they’re exactly the same in that if you’re a subordinate human, your health is generally going to be worse. Much of the poor health is coming out of the psychological mediators of subordination rather than the physical ones. We’ve invented the most effectively crushing version of hierarchical subordination that the primate world has ever seen, which is low socioeconomic status. And that just flattens anything any other primate has come up with for a way of corrosively just sublimating another member of their own species.

So it’s exactly the same with the same physiology until, once again, you look more closely. And one of the key things is that unlike any other species out there, we belong to multiple hierarchies at the same time. What we’re really good at is deciding why the hierarchy where we’re down in the basement is nonsense or whatever, and why the ones in which we’re…. and that’s the world where the person who’s got the crummiest job in this corporation, who’s nonetheless the captain of the company softball team that year. You better bet they’re going to be sitting there saying ‘nine-to-five, Monday to Friday, just a waste of my time, just punching it for the money. Life begins Saturday afternoon when we go….’

We have multiple hierarchies. We have multiple us’s, we have multiple thems, and we’re capable of shifting which ones are at the forefront in a second’s notice.

Dacher Keltner: Yeah, pretty remarkable, isn’t it? I wanted to get your reflections on a very simple statement that you make and you’ve already hinted at it. It actually I think was a pivotal contribution early in your career. In the book, you talk about subordinate rank or subordinate status for a baboon is analogous to learn helplessness and depression in humans, right? And I don’t think people were, in any social biological literature, were really making that case. You were part of a group of younger scholars in the eighties and nineties, Nancy Adler and others, were starting to talk about the toxic effects of lower rank. So where are we today in thinking about that?

Robert Sapolsky: If anything, the picture has just become more convincing and thus more depressing and more outrageous as we find ever new ways in which human subordination in the way of low socioeconomic status just does in your health.

Okay. Two versions. One is a relatively new finding that came out of UCSF and has been replicated since then. It has started a whole cottage industry of work. This is work that was done there by Liz Blackburn and Elissa Epel having to do with these things called telomeres. Telomeres are the ends of chromosomes. It’s virtually required by law that you use this metaphor at this point, which is at the end of your shoelaces, there’s the little plastic cover thingies that I’m sure have a name, but they’re like what telomeres are. Telomeres are at the ends of chromosomes. They don’t code for genes, they just stabilize the whole thing there. And like all of our shoelaces, the little plastic things begin to wear away after a while. With each round of cell division, telomeres get shorter. Finally, when they get short enough, the cell stops dividing, it goes into cellular senescence. This is the nearest thing we’ve got to a cellular pacemaker of aging.

Liz Blackburn, who discovered them, got a Nobel Prize for it, unbelievable work. Then she and Epel, who’s a health psychologist, collaborated in showing that, for example, all sorts of versions of stress in humans accelerate telomere aging. One of the surest ones is low socioeconomic status. God, your position in society, your socioeconomic place has something to do with how fast the ends of your chromosomes are fraying? The other finding with that one is, when you think about it, so outrageous that people should be out singing songs from Les Miz at the barricades or something. You get a kid who’s five years old in this country, and on the average, the socioeconomic status of their parents already predicts their resting levels of cortisol and stress hormones elevated with lower SES, already predicts the thickness of your frontal cortex, the metabolic rate of your frontal cortex, and how good you already are at doing the sort of things the frontal cortex specializes in.

Classic example, anyone here who has been a parent and happens to be halfway as neurotic as I am will have heard of the marshmallow test: these classic studies where you take five-year-olds, you give them a marshmallow, and you say ‘Here’s a marshmallow. I’m going to out of the room for a while. You could eat it whenever you want, but if you hold off and don’t eat it, when I come back to you can have two marshmallows.’ And then you study how long kids can hold out and you look at the different strategies. Go to YouTube. There’s amazing… Kids are hiding them and hiding their faces and kissing and petting the marshmallow and trying not to eat it. And what do you know, with each passing year, you get better at holding out. But what’s most amazing about that literature is how long you can hold out for a second marshmallow at age five turns out to be predictive of things like your SAT scores and your occupational success. And the newest studies coming out from the people who pioneered that show that forty years later, people who were good at holding out for marshmallows have a lower BMI and lower risk of diabetes. At age five, how well your frontal cortex is making you do the harder thing when it’s the right thing to do is already somewhat predictive of this massive trajectory. And at age five, if you’ve been stupid enough to pick the wrong family to have been born into, and you’re already paying a price of SES, you’re already influencing what that arc is going to be. And that’s appalling.

Dacher Keltner: Tough news. And some kids just want to grow up to be a chimpanzee.

Robert Sapolsky: Yeah. But one with a lot of frontal function, which chimps don’t normally have.

Dacher Keltner: So, not only are we interesting in our hierarchies, but you write about how interesting we are sexually. And there are these tournament species with lots of drama and competition. And then there are these pair-bonding species who play the guitar and read poetry to each other. What do you want your kids to be? I mean, you make the case that humans are kind of stuck or were moving or in-between both of these models of sexual relationships.

Robert Sapolsky: You look at these extremes. Literally with social primates, say, you discover some new species, nobody has ever seen it before. And you watch them. If you could see a pair of adult male and female together, and you watch them for fifteen seconds, you already know all about their sex lives, you already know about their reproductive biology, you already know about their levels of aggression. Because basically primates come in two flavors: either pair-bonding, they’re monogamous, they pair for life, very low levels of aggression, males do lots of childcare. South American monkeys who are pair-bonders like that, females always give birth to twins because there’s two parents to take… And then as the other extreme, you’ve got tournament species. Males are twice the size as females, they’ve got big, stupid, hideous, expensive, secondary sexual things, facial stuff, and capes, and stuff like that. And much higher levels of aggression. All females get out of males are good genes with any luck. So that’s what they select for because they’re not getting any parenting skills. Two totally different pictures.

And then you look at humans and by every measurement, every measurement, certain genetic diseases that we have, the ratio of average eyetooth length in male humans versus female humans, every measure tells you, we’re about halfway in-between. We’re about halfway in-between with tremendous individual variation, some of it having to do with say the oxytocin receptor gene and such, which predisposes some people towards more stable relationships. We’re halfway in-between. Like anybody who’s a poet or a divorce attorney could have told you exactly that, which is we fall somewhere in-between.

We’re a confused species. The majority of human cultures over history allow polygamy, yet within most polygamous cultures, the majority of people are in monogamous relationships. The majority of countries that espouse monogamy nonetheless have very high rates at which the monogamous are not really being all that monogamous. And then we go and invent celibacy. None of this makes any sense. We’re totally malleable as a species by every sort of measure of different types of digestive systems, different aspects of cortico. We keep being right there in the middle, which brings us back to the question before. Essentially, what we have evolved to be genetically is the species that is most freed from genetic control of any species out there.

Dacher Keltner: Yep. So quick ending on this, your daughter’s heading off to college and given this confused status of our species, what words of wisdom are you going to offer in light of this science?

Robert Sapolsky: Are you kidding? I would say…

Dacher Keltner: You’re tearing up.

Robert Sapolsky: I would grab this and say, read this book except I just wrote the damn book and I have no idea what the answer is to that one.

Okay. I’m about to become really fatuous. It’s complicated — oh, christ. I paid for a ticket to come to this tonight? — It’s complicated. It’s complicated. Be careful of easy explanations. It’s complicated. Don’t expect to be able to explain any of this effectively by deciding it’s all due to one brain region or one hormone or one gene or one childhood trauma or an evolutionary mechanism. And especially be cautious and be aware of how complicated it is when you think you understand a behavior that you’re judging harshly. Because it’s just fine if we really do not understand the behavioral biology of whether we brushed our top teeth before our bottom ones or the other way around. You know, that’s not a pressing societal problem. But the fact that we are making implicit judgements all the time as to how volitional people’s behaviors are, our worst behaviors, our most damaging ones, our most scary ones. We almost always are assessing them with pitifully incorrect or tiny amounts of biological assessment of how much biology has shaped what’s going on. You know, that’s the domain where you really need to think through this stuff when you’re judging behaviors harshly. That’s where we’ve got to realize the extent to which we are purely biological organisms.

Dacher Keltner: Yeah. So I have one more question on the complicated primate we are, and then we’re going to have a few questions about the good and bad and what your thoughts are. And then we’re going to open it up for some audience questions and answers.

We’re also a political primate and a moral primate. And I want to get your philosophical speculations about some of the findings that you summarize. And I’ll just read them in a neutral fashion about the differences between liberals and conservatives that are being documented in this scientific literature. So it’s interesting, there are these moral foundations that you write about, that John Haidt has written about, about caring, about harm and justice and community, purity, and then authority and hierarchy. What’s interesting there, and it’s been a finding that’s gotten a lot of play, is it really looks like self-identified conservatives speak more moral languages. That liberals really care about harm and justice, but then conservatives really endorse all of these moral foundations. So that’s finding one.

Finding two is that liberals tend to like complexity and uncertainty more, which you write about. Finding three is conservatives get disgusted by a lot of stuff and it drives moral judgment. And then, members of the audience may take heart in this, finding four is –and this is published in one of our best science journals — conservatives just seem more fearful. They startle more dramatically. Their amygdalas are more hyperactive. We talked about that. Then, some of you may take this one home and enjoy it, conservatives have three times as many nightmares as liberals. Now what’s going on here? How do you make sense of this stuff?

Robert Sapolsky: Um, we…

Dacher Keltner: You’ve written Behave, so…

Robert Sapolsky: The rumors of our rationality are greatly exaggerated. I mean, Jonathan Haidt’s work is shown to the amazing extent that we make our moral judgments based on intuitions, implicit biases, gut instincts, and as he shows throwing people into brain scanners, we make our moral decisions in our limbic system and our amygdalan plate on scales of milliseconds. All that our conscious selves do and all that our cortical neurons do often is run to catch up and say, this actually makes a great deal of sense…here’s why that makes sense. I can’t quite put my finger on it, but it’s wrong when they do that. Here’s why it’s wrong when they do that. That we rarely, very readily confuse rationalization with rationality.

Among those, I think the one that I find so irresistible is that business about the role of disgust in political orientation. This has been replicated, this came out of fabulous people at Yale, Paul Bloom’s group there. Take somebody, take people, and sit them down in a room and they fill out a questionnaire about their political stances, about economic issues, about social issues, about geopolitical ones. And if you instead have somebody in a room with smelly garbage in it, people become more socially conservative at that point because you’re confusing the visceral sense of vague disgust with, what social conservative, social progressive issues are very often about is whether somebody who’s different from you is merely different from you or if that’s, in fact, kind of exciting and enriching, or if different in some visceral way means wrong, wrong, wrong. A sense of disgust pushes you in that direction.

The part of the brain that processes sensory disgust — you bite into some disgusting food and this area of the insular cortex, every mammal on earth, what it does is it makes you heave and gag and spit this stuff out. And it’s very adaptive and it does the same thing in humans, but in humans, it does the same thing if you hear about something morally appalling. It does moral disgust, as well, and it intertwines the visceral sense. Drink a bitter drink and people immediately afterward are more condemning of a moral transgression because the disgust, whatever is interacting with that. And it turns out that on the average social conservatives, not economic, not military, social conservatives have a lower threshold for gag reflexes. There are these great studies where you show people pictures of festering wounds and you see how much their stomach lurches. One of the things that leads you towards that, if your physiology is where novelty and ambiguity gets all sorts of visceral alarm signals going off in you, if disgusting things really, really get a strong, visceral response in you, that’s the implicit framework that’s going to make you be the sort of person who rationalizes afterward why it makes sense that they are not just different, but that’s wrong. And it’s running after the facts there to try to make it all make perfect sense. It’s just this subterranean biology rumbling along there.

Dacher Keltner: Yeah. The politics of food and taste. So we’re going to open it up in about five minutes. I wanted to get your thoughts on… because I think what is really remarkable about this book is just the honest grappling with the good and the bad.

You write about the biology of humans at their best and worst. You’re really struck by the us-them distinction. I mean, it just seems to run through a lot of your deeper analysis. The amygdala starts processing faces of different ethnic backgrounds differently or more actively within…

Robert Sapolsky: A hundred milliseconds. The 10th of a second approximately. When you throw somebody in a brain scanner, it’s a literature that’s simultaneously so damn depressing, but if you hang on with it, to the very end actually, has a great amount of room for optimism. The so damn depressing part — our brains process us-them differences on the scale of milliseconds, subliminal signals, it tends to specialize the ones that get the fastest reactions are differences in race, gender, age, status symbols. Our brains are so wired up to distinguish us’s from thems. This we saw before that oxytocin, a hormone, works diametrically opposite on these two different classes of people, these are fault lines deep in our brains. And what do you know? We prefer the us’s to thems and go out of our ways to sort of be miserable to the latter. Oh my god. How inevitable is this? How inevitable? Not at all. For example, the main sort of issue with all of this is I think we are absolutely hard-wired to make us-them distinctions and not like the thems, but we are so easily manipulated as to who counts as an us and who counts as a them.

Take a study where you’re flashing up faces of rapid speed and, oh my god, if it’s a race of a different face, the amygdala activates. Now do the same study and the faces are wearing baseball caps of the… I’m going to embarrass myself here… the Giants? Is that the team here?

Dacher Keltner: Well done. I am glad you’re spending all that time in Kenya in your tent.

Robert Sapolsky: I assume they have a rival.

Dacher Keltner: I’m not even gonna answer that.

Robert Sapolsky: Okay.

Dacher Keltner: The Dodgers.

Robert Sapolsky: The Dodgers, the Dodgers. Okay.

Dacher Keltner: They used to be from Brooklyn.

Robert Sapolsky: Yeah, the Brooklyn Dodgers. So you go out to Ebbets Field and you could see the Dodgers play.

Dacher Keltner: Where you grew up.

Robert Sapolsky: Exactly.

Dacher Keltner: Many afternoons there writing primatologists.

Robert Sapolsky: Apparently not so many. But now instead you flash up the faces and they’re either wearing the cap of the home team or the cap of the hated rivals. And you completely recategorize who activates the amygdala. Ooh, hardwired us-thems along the lines of race and ethnicity. And are we inevitably fated to switch it in two seconds because we carry all these us-them dichotomies in our heads? Which one is at the forefront changes within a second? And there’s some good news in that…

Dacher Keltner: We can put our malleability to good use. So, final question on the good side. Do rats feel compassion?

Robert Sapolsky: Oh, well, I was actually…

Dacher Keltner: We know humans don’t.

Robert Sapolsky: I was actually on a paper once with a McGill group that’s done some work on that, and I was sort of carpetbagging into that study. But they put the word compassion into the title, and we spent about four months fighting with the reviewers who said you can’t put a word like that in there about rats. Compassion-like behavior?

What is clear is we are not the only species that will halt its ongoing activity if another member of our species is distressed. We are not the only species that will exert effort at that point to try to make the other individual feel better. Rats pressing a lever, rats foregoing a reward in order to, say, decrease the shocks on another individual. Probably most meaningfully, we are not the only species who feels that way more for some individuals than others.

With the rats, you don’t get that unless that’s one of your cage mates who you know and like. And what we did in that particular study was show you don’t get that response if it’s a stranger rat. And the reason for it is strangers evoke stress responses. If you block the effects of cortisol on the brains of those rats, they are as empathic to a stranger as they are to someone they know.

Then the coolest thing in that study is that they then did it to college freshmen who they got a hold of — this part I had nothing to do with — where they showed a pain compassion test. I’m not even sure if I read this part of the paper right when they sent me the draft, but they had them play Guitar Hero, which apparently there’s a mode cooperative or whatever, and they showed that your pain empathy for somebody else could be switched either by if you played with them beforehand, you did something collaborative with them, or if you gave them a drug that blocked their stress response.

What that tells us is a lot of the time we’re being crappy to strangers because strangers are scary. Back to the amygdala being much more about fear than it is about aggression, but it’s inseparable.

Dacher Keltner: Yeah. So I’m gonna ask one last question and then we’re gonna open it up for twenty minutes of questions from the audience. Robert will be signing books afterwards out in some part of this building in the lobby, I imagine.

You know, we live in a really interesting time with respect to science. You think about it being the richest time, in some sense, in terms of our scientific understanding of the world. There’s no doubt about that. The knowledge growth is exponential. There’s a lot of hostility within our culture towards evolution and science and the kind of things that you and I do. I wanted you to kind of step outside of the lab. For example, you were brought in to offer some ideas about what to do about the criminal justice system. We have over two million people in prison, it doesn’t seem to be working. So what’s your sort of call to young people who are interested in science and changing the world? What did you sort of learn from that experience?

Robert Sapolsky: Oh, boy. You gotta throw that one at me? So what can you do about this? One of the things I’ve noted is you can’t reason somebody out of a stance that they weren’t reasoned into in the first place. If you don’t recognize the extent to which people are running on fear, fear of the future, fear of the unknown, fear of ambiguity, fear of loss of status, fear of loss of efficacy… that’s the angry white male syndrome in the United States right now when history and technology and relevance have passed you by and outsourced you in every meaningful sort of way. That the undercurrents of biology that are playing a huge percentage of the control in what behavior is popping out the other end is stuff that they themselves would never have a clue is there. And that it’s a real uphill battle to get people to consider that possibility. You mean I just did that because of that? I’ve constructed my whole sense of self-worth, identity, community, belongingness, et cetera, out of, and that was a mechanistic behavior on my part? Yeah.

Dacher Keltner: Yeah. Interesting.

Robert Sapolsky: We like being a autonomous individuals and it’s a tough battle to see that we’re biological organisms instead.

Dacher Keltner: I bet you have a lot of people out here who have been dying to ask Robert a question about stress or Behaveor other questions on your mind. We have one of the real special minds here, so who’s first?

City Arts & Lectures: This question is all the way to your right in the orchestra.

Audience Member 1: Hello. My question is in more conservative societies, which are more, faith-based, more community-based, more family-oriented, has there been any studies about whether there are higher levels of oxytocin with these people? And then along with that, when oxytocin makes people feel like they want to separate from other people, is it triggering a cortisol response? Thank you.

Robert Sapolsky: Great. The second question first. In a lot of ways, this one part of the brain called the anterior cingulate is very centrally involved in empathy and compassion. Literally poke your finger with a pin, anterior cingulate is one of the areas that activate; poke the finger of your loved one with a pin and anterior cingulate is the main area that activates. That’s where you feel somebody else’s pain as much as your own. That turns out to be an area that’s a hotspot for both oxytocin’s working and cortisol working. And they’re generally working in the opposite directions. Absolutely.

Next in terms of the question: cultures that are more cooperative and egalitarian and commendable and kumbaya-ish and whatever. Do they have higher levels of oxytocin? I don’t think anybody has looked at it yet, but my guess is no. And this is one of the things that I had to kind of work my way through, the ways in which an awful lot of this biology is value-free.

What do I mean by that? Depending on the circumstance, testosterone could make you violent and appalling, or it can make you more cooperative. Your frontal cortex is really, really useful for keeping you from lying in some tempting circumstance. But once you decide you’re going to lie, your frontal cortex is essential for you doing a good job at it.

It can take a spectacular theory of mind to understand somebody else’s pain in order to find the most effective way to comfort them. It takes spectacular theory of mind to be a manipulative sociopath. It takes neural plasticity to learn how to be a saint or learn how to be a nightmare. And all of these are value-free in a certain level.

One of the things that I’ve had to sort of work through is the recognition that, like in an awful lot of scenarios, the bad guys have no less of a sense of group membership, group self-sacrificial nature. I mean, this is something you absolutely tap into in terms of what power does in terms of influencing a group. A really striking version of this is Robert Coles, the Harvard sociologist psychologist, who in the sixties did all sorts of these studies of children in the American South, African-American and white, growing up amid the segregation battles. One of the most insightful and empathic things he did was point out that kids on both sides of these divides were equally self-sacrificial and were equally willing to forego health and safety in the case of the African-American kids, and the white kids, who were being sent off to these jury rigged all-white academies that were being set up in somebody’s outhouse, overnight kind of thing. That the parents were perfectly aware that this was compromising your kid’s sort of edge, but both sides had an air of righteousness and both sides were willing to suffer for it, and both sides were probably running on in-group oxytocin like mad. These biological influences are so context-dependent that very often it’s the exact same biology underlining our best and worst. Elie Wiesel, his famous quote: “The opposite of love is not hate. The opposite of love is indifference.”

Biologically, love and hate have a whole lot more in common than either has with indifference.

Dacher Keltner: Wow. Yeah. And it’s interesting Alan Fiske has been writing as well, and you have a lot of interesting counterintuitive twists on the things that we should be wary of, and one is feeling like things are sacred, right? That it’s totally context-dependent. We can imbue any kind of object with the sense of sacred, and then we’ll do anything, even genocide, in the service of that. And Alan Fiske has been making the case down at UCLA that a lot of the violent genocidal tendencies people do not out of immorality or a different kind of biology, but one out of love and the sense that it’s sacred and righteous. So, it’s worrisome.

Robert Sapolsky: Sacred things are not just saffron-colored rooms. People kill and are willing to die for their sacred symbols, which, from a distance, makes no sense whatsoever.

Dacher Keltner: Next question.

City Arts & Lectures: This question is in the balcony at the center about halfway back.

Audience Member 2: I’m just wondering about your theory on adoption. Genetics versus environment.

Robert Sapolsky: Okay. Oh, god. Such a messy subject. This was the one chapter that almost ground this book and me into a complete… okay. So, genes and behavior. Behavioral genetics. Just the basic organization of the book very briefly is somebody does a behavior, it’s an appalling one, it’s a wonderful one. It’s the ambiguous ones that are mostly in between in the eyes of beholders. Why did that behavior occur? Why did it occur one second before? What went on in that person’s brain? Minutes before what went on in the environment that triggered hours to days before? What did the hormones due to the sensitivity to those environmental stimuli that cause… all the way back to evolutionary history.

So, way back, most of the way there is what genes have to do with behavior. There is no subject in the field of behavioral biology that has been more contentious and more inflammatory and more just begging for pseudo-scientific distortions and begging for, in some historical cases, pseudo-scientific distortions that involve things like lobotomizing people or sterilizing people or sending people off to gas chambers.

In all those cases, there’s this enormous complexity built around how controlling are genes of our behavior. One of the most complicated areas out there are looking at studies of twins and studies of adopted individuals. Behavioral geneticists drool with pleasure when they get ahold of somebody who was adopted within minutes of birth, because then what you can do is see what traits they have more in common with their adoptive parents or their biological parents. Biological parents, they weren’t raised by them, so all they got was genes from them. All they got from the adoptive parents was environment. And if you see a difference, if you see something more shared with the biological parents, you’ve just uncovered a genetic difference. That was the first thirty years of rationale for that entire field until people discovered, ‘Oh, uh oh, prenatal environmental effects.’

As we heard already, you have a big amygdala and they go back and they find that your biological mother had a big amygdala, obviously caused by genes. Not obviously caused by genes. If you have a big amygdala, you’re going to secrete more stress hormones, which are going to marinate your fetus during their time of the womb, which is going to cause them to have a bigger amygdala. A trait passed on from your biological parents, which have nothing to do with genes.

So it’s this insanely complex field looking at one third of identical twins have separate placentas and two thirds of them share them. Thus the prenatal environment they have is more similar and you’ve got to control for all this stuff. And at the end of the day, what that massive literature shows is that genes have something to do with some of the most boring sledgehammer traits we have out there. If you’re interested in humans being kind and unkind…schizophrenia, alcoholism, big massive manic depressive disorder. If you’re trying to figure out does any of this tell us the genetics of somebody who’s very compassionate and very charitable, but they usually do it in a passive manipulative way, but then they kind of feel badly about it afterward, but then they usually sort of cover it up because they’re embarrassed by this. No, we’re not within light years of having any insight into what the genetics of that is. And that’s the genetics of all this interesting stuff. Figure out the genetics of the vast majority of us who can say, ‘Yes, this is absolutely wrong. This is not something people should do. This is absolutely wrong, but here’s why this is a special circumstance for me and why this should be an exception.’ The road to hell is paint with rationalization. And the neurobiology of that is going to be trivial compared to the genetics of it. So the field is moving very slowly and with enormous complications and very smart, contentious people working really hard to controls. And there’s a glimmer of insight into behaviors that are just sledgehammers of crudity compared to the stuff most of us are interested in.

Dacher Keltner: So I’ll ask you a final question and then say thank you. So this is a big book and one of the big themes that you take on is something that Steve Pinker took on with The Better Angels of Our Nature, which is, you know, where are we going? Given our biology and given the complexity of who we are and given culture, gene interactions.

Robert Sapolsky: Well, if your basic makeup is to be optimistic, which I’m not, but if your basic makeup is, it comes much more easily to have to accept that the world really has gotten a whole lot better in the last 500 years and in the last couple of centuries, and this is the realm that Pinker covers brilliantly in that book of… you know…1800, slavery was universal, child labor was universal. There was not a place on Earth that sort of regulated abuse. Now, it’s virtually universal for countries to at least pay lip service to such things. Obviously, massive abuse is obviously naive to say, but nonetheless, that’s a whole lot better.

20th Century. Look at some of the things we invented: world courts, the notion of crimes against humanity, treaties that certain types of killing people were bad, organizations where you can give money to them in order to save people on the other side of the planet, adopt people on the other side of the planet, the UN having an organization where it would send soldiers to places on Earth to stop people from fighting. All of these were concepts in the last century. And our mindset is extraordinarily different from 500 years ago and from 200 years ago. What Pinker calls the Rights Revolution, all the reasons why in which we’ve been able to extend umbrellas of protection and recognition and compassion and all sorts of new directions. If we don’t blow ourselves up or fry our planet or all those things, it seems like there’s a vague reason to think that this trend will continue. I mean, that’s about as optimistic as I can imagine, but for my… given my channel makeup, that’s practically me levitating here for meditation.

Things have gotten better and the mechanisms to transmit doing good are better. All of that is within the framework that the village bully, who would’ve taken a cudgel to three people’s heads now has an automatic weapon. Lone wolves can find themselves and each other online. Awful people can now travel the world, you know, all of that. But nonetheless, it’s lots of room for optimism and there’s a whole lot of science that I think gives us some insight at some of the levers that make those outcomes more likely.

Dacher Keltner: So Robert is going to be outside, signing a book that will break your addiction to CNN. Thank you.