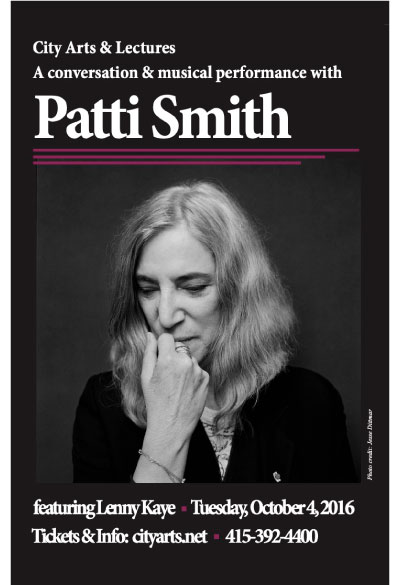

Dan Stone: Hey, everybody. Welcome to City Arts and Lectures. I’m Dan Stone. I’m really happy to be here with you tonight. Thank you so much for coming. We’re gathering together tonight for a good cause. This event is part of City Arts and Lectures’ program, On Arts, which benefits the 826 Scholarship program. Yeah, another good program by 826. So by being here tonight, you guys are helping kids access and attend college. Absolutely. We’re thrilled to have Patti Smith—the multitalented Patti Smith—here with us tonight. She’s here on the occasion of the paperback publication of M Train, which is the follow-up to her 2010 National Book Award-winning, Just Kids.

M Train is a strange and gorgeous book. It’s sort of a meandering meditation on loss and art and travel and the routine of daily life, and also on Patti’s hopeless addiction to her drug of choice: coffee. So, we’re going to drink some, and let the conversation wander and we’ll save some time at the end for audience questions and some songs.

Please welcome back to City Arts and Lectures, the punk poet laureate, Patti Smith.

Patti Smith: Hi, Dan.

Dan Stone: Hi, Patti. Welcome. Really good to have you here. Thanks for joining us.

Patti Smith: Thank you.

Dan Stone: I have been hyper-caffeinated for the past couple of months while preparing to talk to you, ’cause you can’t really read this book without drinking coffee. So I actually made a pot and brought it from home. Would you like some?

Patti Smith: Yes, yes.

Dan Stone: We can have some while we talk.

Patti Smith: Well, coffee with a handsome guy, what could be better?

Dan Stone: Thanks. Throughout the book, you’re drinking coffee—good coffee, bad coffee—in your favorite cafes around the world, at 7-Elevens, New York delis, hole-in-the-walls in Chinatown. You don’t really discriminate, and I really love that about your relationship to coffee, because so many people who say they love coffee are snobs, but you’re not.

Patti Smith: Well, when I was young, I was a coffee snob and I did the ultimate thing: I went to Veracruz and then into the nearby mountains and I had coffee that they grow in small quantities, and they’re entwined with orchids and they only make like, you know, eight pounds a year of it. So I’d already done that a long time ago and nothing could top that, so now I’m just happy with plain old deli coffee.

Dan Stone: That’s one of my favorite parts of the book is this trip you took. And if I remember, it was on a recommendation from William Burroughs that you had down there. Could you tell us a little more about that experience of wandering around that town some decades back by yourself?

Patti Smith: When you’re young, I mean, I didn’t have any fear. I couldn’t speak Spanish. I just knew I had to go find this coffee that William said was the best coffee in the world. I was going to write this book called Java Head, and so I went and I found this little tiny place where they distribute the coffee and it was a little hole-in-the-wall with burlap bags and the finest coffee beans in Mexico. Just men with cigars. And I wandered in with my Ray Bans and my trench coat in August.

And I told the guy—the guy spoke English, so I was lucky—I told him that I was working for “Coffee Trader Magazine” and that I had to write something about the coffees. So for three days I just sat there all day long writing poetry and drinking all kinds of coffee. And at the end he brought me the coffee, the William Burroughs coffee, because you can’t actually go way up there where it is, cause it’s forbidden and secret. And it really was coffee laced with orchid pollen. It was mystically beautiful. I was only 22, but I knew that I would never have another cup of coffee like that, so it was over. No, I’m just joking. I was in tears, it was so beautiful.

I still to this day really like Mexican coffee, but I’m happy with Italian. That Illy, I-L-L-Y, is that how you say it? They always make good coffee. But I’m like, at this point in my life, I’m not even supposed to drink coffee, so I just usually have coffee and then I get a lot of hot water and water it down and then I can drink that all day. So, I really drink diluted coffee. Not ‘deluded’ like delusional, more like—

Dan Stone: —Watered down.

Patti Smith: Diluted, yeah. Here’s to you, Dan.

Dan Stone: Yeah, cheers.

Patti Smith: Good.

Dan Stone: Thanks. Somebody told me the other day that there was a practice—and I’ve not been able to find anything about this—that if you were drinking really bad coffee, add salt to make it palatable.

Patti Smith: Yeah, I heard that.

Dan Stone: Have you ever tried that? I thought of grabbing the worst coffee I could find in the neighborhood and trying it with you, but I didn’t have time to find it.

Patti Smith: I wouldn’t have known the difference, probably. I’d have just poured hot water in it. I don’t recollect trying it. Also, too much salt isn’t good for you. It’s better just to get better coffee.

Dan Stone: Yeah, absolutely. You also spend a lot of time in cafes in the book, particularly writing in cafes, which is something I like to do as well. What makes a good cafe, a good cafe for working in?

Patti Smith: Well, these days it’s getting harder and harder because the concept of “cafe” is changing. Now people like to use cafes as their office, so they bring two or three devices and they’ve got their earpiece and they’re arguing about stocks or whatever. It’s an agitated energy with a lot of technology, and people look at it as sort of a workplace. It used to piss me off, but then I think, what was I doing? I like to go to a cafe where there’s people there and there’s sort of a hum of energy, but not too much energy. And you can drift off in your own world and read or write and drink coffee, but you still have humanity around you because writing is so solitary and sometimes lonely. So to go in a cafe that has sort of a low-key, cool atmosphere and still have a sense of humanity around you, but you can still do your work. And it doesn’t have to be really fancy or anything, or it doesn’t have to have rare Tabriz rugs or pictures of poets or anything. It could have linoleum floors and little tables. It’s more the atmosphere in the cafe.

Dan Stone: You almost don’t want it to be too good. And you definitely don’t want it to be popular. And that’s a problem I have, I live in Oakland, there aren’t any cafes near me that are unpopular and crappy, and that’s all I’m looking for: is it kind of a bad, unpopular cafe?

Patti Smith: When I get older, you know, like 90 or something, someday I’m going to open my own cafe and it’ll be very unpopular.

Dan Stone: I promise I won’t come.

Patti Smith: Because all it’ll have is like, black coffee. My idea would be to have a cafe where it just has black coffee and it could have an oven and just make loaves of brown bread or something like that. And some little plates of olive oil, but don’t ask for nothing else. That’s my idea of a cool cafe.

Dan Stone: I like that. You write early in the book that at one point you almost did open a cafe. You dreamed about it for a while.

Patti Smith: Yep. Actually, ’cause you’re talking to Bruce tomorrow—was I supposed to say that? I didn’t know if it was a secret or not. But Bruce Springsteen and I did write that song—well, it was more Bruce—but we did “Because the Night” and it was very successful and I made little money from it. So I took that money and I put a deposit on this dilapidated place in the East Village, and my brother and I were going to make it into a cafe. And just at that moment, my fella who lived in Detroit decided it was time to ask me to come to Detroit and stay with him.

So I was like, you can’t have it all, you know? Was I going to have a cafe in New York and do other stuff, or go to Detroit? So I opted to be with him. So that was as close as I got. But I have to say, for the two months that we were painting it and I had a little card table and I would sit there with coffee to go and daydream about this and that… But truthfully, I had everything ready, but we didn’t have enough money to buy a big coffee machine. So I’m not so certain it would have worked out anyway. Sometimes dreaming is good enough, you know?

Dan Stone: Yeah, sometimes that’s all you need is to develop that idea. Like with your late husband, Fred Sonic Smith, he developed that idea for the TV show, “Drunk in the Afternoon.” You guys bought a boat and spent a lot of time restoring it, but never took it out.

Patti Smith: Yeah, it had a broken axle. He really wanted to get an old Chris-Craft and we didn’t have much money. He found this beautiful old 30 foot Chris-Craft with a trailer for not much money, and we bought it and we took it back to our house near Detroit and we put it in the backyard. We lived on a canal, so we were gonna put it in the water. And we worked on it, sanding it and cleaning it, and I made little curtains. I’d never made a curtain. I can tell you exactly how to make a good curtain. What you do is you take a piece of cloth and then you fold it over on the top and the bottom and sew it, but leave enough space to put a little pole in it and just hang it up.

So I made curtains. And then we had to have it inspected, but it turned out it had a broken axle and it wasn’t seaworthy, so we just used it to listen to Tigers games. I’d make a thermos of coffee and he’d have a six pack of Budweiser and we’d take the transistor radio and go in the boat and listen to Tigers games

Dan Stone: That’s what I want to do every afternoon. That sounds amazing.

Patti Smith: Yeah, it was awesome.

Dan Stone: I wonder if I could ask you to read something. We were talking about working in cafes. There’s a passage about work life at home. Domestic work life. Just a short paragraph, it’s on 72. Do you have your book with you? You can use this.

Patti Smith: Yeah, I can use yours.

Dan Stone: Let me find it, this beautiful little passage about a life of work—

Patti Smith: —Was that in Michigan?

Dan Stone: No, this is New York. Oh, no, you’re right. I’m sorry. This is Michigan. Yeah, starting at the bottom there, it says Michigan.

Patti Smith: Oh yeah, I see what happened. It does start in Michigan and then it goes into New York.

[Reading] Michigan. Those were mystical times; an era of small pleasures. When a pear appeared on the branch of a tree and fell before my feet and sustained me. Now, I have no trees. There is no crib, no clothesline. There are drafts of manuscripts spread over the floor where they slipped off the edge of the bed in the night. There is the unfinished canvas tacked to the wall, and the scent of eucalyptus failing to mask the sickening smell of used turpentine and linseed oil. There are telltale drips of cadmium red staining the bathroom sink along the edge of the baseboard or splotches on the wall where the brush just got away.

One step into a living space, and one can sense the centrality of work in a life. Half-empty paper coffee cups, half-eaten deli sandwiches, an encrusted soup bowl. Here is joy and neglect, a little mezcal, a little jacking off, but mostly just work. This is how I live, I am thinking.

Dan Stone: You’ve talked about this book as being the most accurate description of how you live.

Patti Smith: Yes.

Dan Stone: I always think of that passage. What’s your routine like now? So much of the book is about daily routine. How do you spend your days?

Patti Smith: Well, when I’m home I wake up, say, seven/seven-thirty, and you know, get myself together, feed my cat. And then there’s a place across the street that opens at eight and from eight to ten, it’s pretty empty. So I take my notebook and some book I’m reading, and then I alternate between reading a little and then writing ’till about ten. And then I go back home and start my public day, where I have to answer people’s messages or see what my kids need—things like that. And sometimes go to appointments, like get my teeth cleaned and go to get acupuncture or something like that. And have lunch. Then I usually write throughout the day, but around eight o’clock or nine—depending on the day and what the TV schedule is—I get ready for my detectives. Sometimes if I’m lucky—I think it’s Monday night, maybe it’s Tuesday—there’s three great shows. There’s Miss Fisher’s Mysteries, Father Brown, and then Luther. If there’s nothing good on, I have [Acorn TV], and then I can watch Inspector Morse or Lewis. All my boyfriends.

Every once in a while I go to the opera or something like that, but the routine in my life is really the early part. That’s the sacred time when I like to get up early and write. It’s when the mind seems the most glittering, the most resonant. That’s when I do a lot of my writing.

Dan Stone: Yeah. That’s my best time, too. I’m always fascinated by people who start working at eleven or midnight.

Patti Smith: Well, when I was younger, I used to sit up all night writing poetry and I thought I was so cool. But then when I had children, that was impossible. I had too much responsibility, so I had to develop a new routine. I found that from five in the morning till eight in the morning, when everybody was sleeping—my husband, the kids—that was my time. And it took a while to get used to writing at five to eight in the morning, but after I got in a groove, I maintained that discipline and I have it, still. I mean, I wasn’t happy with it at first, but now it’s one of the best things that I’ve maintained since like 1982, that concentrated time for writing.

Dan Stone: Yeah, that discipline. You travel a lot in this book, and one of my favorite moments happens in Iceland. I was wondering if you would tell us this story, when you—speaking of midnight—had a midnight rendezvous with Bobby Fischer, the great chess player. It’s an incredible moment. Would you tell us how that came to be and what it was like?

Patti Smith: I was playing in Iceland with my band, and then I stayed on for a while ’cause I wanted to ride horses. I like the Icelandic ponies. But I was also obsessed with taking a photograph of the table that Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky had their great match on in 1972. And it turns out that the Icelandic government had it in the basement. So they said, all right, you can take a picture of it, but we need you… Well, various things. I don’t want the story to go on too long. I just wound up moderating a chess match. If I moderated the chess match, I could photograph the table. I was a little worried since I don’t know how to play chess, but I went anyway and it turned out it was a bunch of 12, 13 year-old geniuses. It was all kids, and they’re all fantastic chess players. So then this one girl, she’s like, 12 and a half, and she challenged me to play chess with her. And I said, ‘You know, I have a feeling you would win anyway, so let’s just get ice cream.’ Everybody was happy with that.

So we got our picture taken together, and there in the forefront was the table. And in the article they wrote about how I had really come to photograph this table. The next day, it’s in the newspaper, and I get this call from this guy and he tells me that he is Bobby Fischer’s bodyguard, and that Bobby Fischer wants to meet me, but it had to be secret. Nobody could know about it. It had to be midnight. It had to be in the closed dining room of a certain hotel in Reykjavik, and I was allowed to bring my bodyguard. As if I got a bodyguard, you know, it’s like, who’d want me? I mean, really. I really don’t need a bodyguard and I certainly don’t have any big jewels that anybody is going to be after.

So anyway, I asked my guitar tech if he would come. So me and my guitar tech show up at midnight and we both have hoodies. It’s sort of chilly. And here comes this bodyguard, who’s like six-foot-four, with Bobby Fischer, also in a hoodie. We all looked like Bob Dylan in the nineties. So my guitar tech, who’s five-nine, and this other guy, six-four, are standing outside the door so nobody can get in. And me and Bobby Fischer are in this room together and he sits across from me and he immediately starts being totally disgusting. Saying dirty stuff, and anti-this and anti-that. And I said, Bobby, you don’t know who you’re talking to. You want to be disgusting? I can be twice as disgusting as you.

Oh, and I forgot: the main rule was that I was not allowed to talk to him about chess. I was so glad because what was I going to say? “Oh, how about that pawn on the three move?” So anyway, I said that to him and then he looks at me and I thought, He’s going to leave. And then all of a sudden, really seriously, he says, “Do you know any Buddy Holly songs?” And I said, yeah, so I start singing a couple of Buddy Holly songs. He starts singing with me and I have to say: genius chess player, really bad singer. But that’s what we did all night long. We sang everything: songs of The Chi-Lites, The Isley Brothers. Like, “Oh, do you remember this one?” “Rag Doll,” every single song you could imagine. Rockabilly songs, ’till three or four in the morning. And then, as the dawn was approaching, he got up, put up his hoodie and he left, and me and my guitar tech went off into the sunset. Sorry that took so long.

Dan Stone: No, it’s a great story. And you gave a lot more detail than you do in the book. I love the moment in the book, too, where his bodyguard bursts into the room when Bobby Fischer jumps into falsetto to harmonize with you at a certain point.

Patti Smith: Yeah, Bobby’s singing falsetto really bad, [singing] “Big girls don’t cry…” you know, really, really, bad and—this is a true story—the bodyguard ran in and he goes, “Are you all right, sir?” and Bobby was really crushed. He said, “I was singing.” I don’t think the bodyguard guy ever heard him sing. The bodyguard was also a chess master.

Dan Stone: I’m fascinated by your photographing that table, the chess table. You do a lot of this, where you travel to get a photo of a thing, a charged thing. You mentioned Herman has his typewriter, a lot of the Polaroids are reproduced in the book—what draws you to photograph? Well, first, let me ask you about photography. You write in Just Kids that you were always encouraging Robert Mapplethorpe, who’s at the center of that book, to take his own photographs. I don’t think in Just Kids you take photographs, but by the time you have reached the stage in your life that you’re writing about in M Train, you’re a photographer, particularly Polaroids. So when did you start taking photos and what led you to that?

Patti Smith: Well, I never would consider myself a photographer, or at least I would consider myself an amateur photographer, but we took a lot of pictures when I grew up. My dad made Pentaxes for Honeywell, so cameras were around and I used to take photographs, but mostly to use as information in big drawings or something. I wasn’t ever that seriously interested in taking my own pictures, but after Fred passed away in the end of ’94, and then my brother, I was so emotionally exhausted and physically exhausted, and I had my kids, and I couldn’t do anything. I couldn’t write, I couldn’t draw. But just because of the kind of person I am, I really had a need to do something, to do some kind of work, to do something of worth. And of course, taking care of your kids, there’s nothing more worthy than that. But I needed, as a worker, to be doing something.

One day, Fred’s Polaroid camera was just sitting around and it had some film in it. So I made a little still life. I had a pair of Nuryev’s practice slippers, which I own, and I took some mosquito net and then I made sort of a little tableau, and I took a photograph of it and I really liked it. And the thing with a Polaroid, you peel it off and you have it. So I took one picture and it gave me an instant feeling that I did a piece of work. And then I started doing that, just one a day or two a day. And it sort of satisfied my need to do something until I was able to… It took a long time for me to get my energy back and get back to work, but it gave me something and then I just kept taking them. It’s sort of a friendly addiction, taking the pictures.

I’m not trying to motor drive or take a million pictures, I’ll sort of get an idea or a desire. And it’s like a whole package. Like, Herman has this typewriter. I really wanted to take a picture of the typewriter he wrote The Glass Bead Game on. So I wrote the Herman Hesse Foundation, and they’re in Lugano in the Swiss-Italian border, and they don’t have a whole lot of money so they asked if I would do a little benefit there. And I said yes. I came and did a little benefit. And in exchange they let me photograph his things. And so it becomes an adventure. And I got to go there, I got to see the house and where he lived and his spectacles and things like that. And I got to take a photograph that I was really happy with. So, you know, it’s become sort of an adventure. I mean, I live alone, I don’t have a companion, so all of my journeys I’m by myself. It sort of would feel stupid to go on, what, a singles vacation or something. But it gives me a goal, a mission, and that is satisfying. And then if I get a good picture, I can share this experience with other people.

Dan Stone: It’s a really beautiful way to travel. You did the same thing in Mexico when you went to Frida Kahlo’s house and gave a talk, or participated in a conversation so you then could photograph her things, or as part of your reason for going.

Patti Smith: Yeah, I trade.

Dan Stone: And the same thing in Iceland, you moderating the chess match.

Patti Smith: I like the barter way of living. I do that a lot. Sometimes I’ll be traveling and I’ll have my little guitar and sometimes I’ll just forget my money in a hotel or something. This especially works in Italy. You can go in a little pizzeria or something. They’ll go, “Patti, hello, ciao.” And I’ll say, look, I forgot my money. What if I sing a couple songs? Will you make me a pizza? And he’ll go, “Patti, of course.” And then I sing a couple songs and he makes me a pizza and everybody’s happy.

Dan Stone: That’s great. I like that. I was inspired by reading about the way you take photographs, and so while re-reading M Train, I bought a little Polaroid. I have a one and a half year old and I’m trying to get him interested in taking photos, although he doesn’t care or understand the process of taking the photo, but he loves these little credit card-sized Polaroids. So, really inspired by your book, we wander around our neighborhood. One roll is 10 shots. So we’ll go out and take 10 shots. I’ve been enjoying doing that, but I haven’t gotten to travel since I started reading your book. It just seems like such a great way to travel, like you photographed Sylvia Plath’s grave—you went to the cemetery with the intention to visit, but also to get one great representative photo of the experience.

Patti Smith: I don’t even think it out that much. It’s really a visual thing, you know? If I analyzed it, you could say that I want a relic, some type of Catholic thing, although I’m not Catholic. It’s like when pilgrims—they do this thing called The St. James Way—they go from church to church to church in Spain and in each place, they get a little medal or a medallion or something to put on their rosary. It’s like my Polaroid rosary, I go from place to place. And I say that with all respect. They’re like my relics of a visit. Also, truthfully, it’s part of the self-centeredness of an artist. You go somewhere and you’re not just happy just to be there, you have to immediately write a poem about it or take a picture of it. It’s sort of the blessing and curse of being an artist: you just can’t relax. But, it’s satisfying. It just makes me happy. That’s what I do, I’ve done it all my life.

Dan Stone: You’re sort of like a living embodiment of one of those literary Almanac calendars. You’ll wake up every day and you’ll say it’s so-and-so’s birthday, or this important thing happened on this day, and you’ll set off about your day with that as part of—

Patti Smith: —I’ve always been like that, too. When I was really young, I loved Willem de Kooning and his birthday was April 24th. So when I was 15 or 16, I started sending him birthday cards every year. Then when I was about 22, Bobby Neuwirth took me to see Janis Joplin at Central Park, and it got rained out and we all wound up at this artist bar—not a place I would have gone on my own, but I was shepherded. I had a good person take me. There was all these famous artists and stuff, and amongst them all, there was Willem de Kooning! I was so excited to see him. I think it was in May or June, and when I saw him I thought, oh my gosh, I didn’t send him a birthday card this year. So I just went up, and I remember he was sitting with Dean Stockwell, who was in The Boy With Green Hair. I was double star struck. I mean, I was about 23. So I said to him, “Mr. De Kooning, I’m so happy to meet you,” and told him how much I loved his work. And then I said, “I forgot your birthday this year, but happy birthday anyway.” And he looked at me and he said, “Is that you?” He got my birthday cards every year.

I don’t know if that’s exactly what you were talking about, but…

Dan Stone: No, no, it is! I partly bring this up because I noticed that today is the fourth anniversary of the day you bought your Rockaway Beach bungalow.

Patti Smith: That’s right. Oh my gosh. You know, I knew it was a special day. Yesterday was the passing day of St. Francis. So I knew that, and I thought, October 4th, there’s something about it. Thank you. That’s so nice that you remembered. How did you—

Dan Stone: —You gave the date in the book.

Patti Smith: That’s so nice, though. It happened to me and I didn’t remember. That’s really nice. Thank you, Dan. That’s so nice.

Dan Stone: No problem. I don’t have a memory for those things, but I looked up if there were any births or deaths today as well, just cause I thought you would know. Janis Joplin died today. It’s the anniversary of her death. And Glenn Gould and Rembrandt.

Patti Smith: They all died today? Cause I’m so birthday—

Dan Stone: —and Anne Sexton.

Patti Smith: Wow. I love all those people.

Dan Stone: I had seen that you did, so I figured you would have started your day thinking about that.

Patti Smith: Oh, what a special day. Well, every day is special in some ways, but that’s so nice. I’m so happy. I can’t wait until this is over so I can think about it.

Dan Stone: Do you still have the Rockaway Beach bungalow?

Patti Smith: Yes. In fact, in the paperback version of M Train… If you already have the hard cover and then you got stuck with the paperback, it’s not really so bad because I worked really hard to put a new cover on it, a new backup picture, and there’s 20 extra pages and my new experimental photography: six cell phone pictures. That’s because there’s no more Polaroid film, but of these six cell phone pictures, one of them shows the actual hospital name tag that I had to wear when I did my cameo on The Killing. So that’s worth having right there. But yes, I have my house. It’s all fixed. It took a couple of years because it got really damaged by Sandy. In fact, it went from being a dilapidated bungalow that at least was like this to one that was like this, but it’s all fixed. I write there and it’s awesome.

Dan Stone: That’s great. I didn’t see Rockaway Beach before Hurricane Sandy wiped out the boardwalk, but I did go there this summer for an afternoon. What’s the scene like there now, compared to when you bought that bungalow? Have they rebuilt it pretty similarly?

Patti Smith: Well, it’ll never be the same. I bought this little place because nobody went there and it had the most beautiful boardwalk in America. It was the longest boardwalk, made of teak, built in 1920. And I totally fell in love with this boardwalk. So I bought this little dilapidated house, which was only across the street from the sea and a block away from the subway. And there wasn’t much happening there except for some surfers and people, families––very diverse place. And then Sandy came and ripped the entire boardwalk out, destroyed the whole boardwalk. And I have to say it was almost like a human being had died. I was so sad to see the boardwalk destroyed. And my little house…

I’m like, the worst person for investing. I predicted that the color TV would never last and that cell phones were a fad. But I got this little place, and it was so dilapidated that I couldn’t get insurance on it until I fixed it. And then Sandy came and completely wrecked it. So as an investment, it wasn’t probably wise, but I love it. We fixed it. We fixed it up. It’s all right.

Dan Stone: We’re going to go to questions in a minute, but I want to ask—Lenny Kaye will be coming out to play some songs with you later—so I wanted to ask about the first time you performed with him, at the St. Mark’s Poetry Project in New York, I think 1972. Would you tell us about that day as a way of introducing Lenny, who’s coming out later?

Patti Smith: Sure. I’d met Lenny because I read this piece he wrote on acapella music, and that was 1970. And back then, you know… I thought, well, this is really such a beautiful piece, so I wanted to tell him but I didn’t know who he was. So I looked up his name in the phone book and I just called him. He told me he was working in a record store not far from me, and I was working in a bookstore. I went to visit him at the record store, and we’re the same age—actually, born three days apart—and we hit it off. We were listening to oldies and dancing in the record store. He told me he played some guitar. At the time, I was seeing Sam Shepard and I was going to have to do my first poetry reading. I had seen a lot of poetry readings and truthfully, they were really boring. I really didn’t want to have to do a boring poetry reading. I wanted it to have some other kind of energy. And so Sam said to me, why don’t you have somebody play guitar with you, or improvise or something? I said, well, I know this guy that says he plays some guitar. So I asked Lenny if he would play and Lenny got his electric guitar and a little tiny amplifier and brought it to the church. And we did our thing.

It turned out it was quite controversial, playing electric guitar with poetry. Some people found it very offensive in 1971. In any event, me and Lenny stayed friends since then. We’d do stuff back and forth and eventually, organically, we evolved into a band. We’re still friends, we still play, and both still write. So that’s the me and Lenny story.

Dan Stone: What’s your relationship now to the musical side of your career? As that story proves, it sort of started as a way to make a poetry reading less boring. Is music still related to your work as a poet?

Patti Smith: Not particularly, except I find that poetry seems to penetrate everything I do, whether it’s prose or writing non-fiction. I wrote so much poetry when I was young, it’s part of the foundation of what I do. It permeates some of the song lyrics, but at this time in my life, I find that the most gratifying or the most important part of music isn’t really writing songs or recording, although I’m very happy to do that, it’s really performing. Performing for the people. It’s just something that I never really had a desire to do. It just turned out [to be] something that I know how to do. I was from a very lower middle class family. We lived in a rural community, nobody got out of there. I wanted to see the world, and I didn’t really have any particular skills or incredible gifts, could never get a scholarship. I didn’t really excel in anything that one would think would send me into the world. And just by accidentally having a rock and roll band and doing Horses, we suddenly were asked to tour, and just like that, I started seeing the world. Because of that, I’ve seen a lot of the world and I’ve communicated with people all over the world. It’s quite an unexpected privilege. So that’s what music means to me now. It’s really communicating with people.

Dan Stone: Right before we go to questions, could I ask you to read one more passage?

Patti Smith: Sure. By the way, you’re really nice to talk to.

Dan Stone: Thanks. I appreciate it.

Patti Smith: It’s not always the case. Believe me.

Dan Stone: This is just a single paragraph, and it starts at the bottom with, “I believe in movement”… I don’t think it needs an introduction.

Patti Smith: [Reading] I believe in movement, I believe in that lighthearted balloon, the world. I believe in midnight and the hour of noon, but what else do I believe in? Sometimes everything, sometimes nothing. It fluctuates like light flitting over a pond. I believe in life, which one day each of us shall lose. When we are young we think we won’t, that we are different. As a child I thought I would never grow up, that I could will it so. And then I realized, quite recently, that I had crossed some line, unconsciously cloaked in the truth of my chronology. How did we get so damn old? I say to my joints, my iron-colored hair. Now I am older than my love, than my departed friends. Perhaps I will live so long that the New York Public Library will be obliged to hand over the walking stick of Virginia Woolf. I would cherish it for her, and the stones in her pocket. But I would also keep on living, refusing to surrender my pen.

Dan Stone: Thank you, Patti. So, the house lights are going to come up and there are two people out there with microphones. So raise your hand and they’ll bring it to you. If you could, please ask questions instead of stories.

City Arts & Lectures: This first question is all the way at your right towards the front of the orchestra.

Audience Member 1: Hey there, Patti. My name is Todd and I’ve been loving your work since you first started doing music. I got into your writing later, but I remember seeing you in the mid-seventies, in Buffalo at Buff State. I brought with me a book of yours, a book of your poetry called Witt. Is that how you pronounce it? There’s a weird accent over the “I”.

Patti Smith: It’s white. It’s like, white/wit. But not white like color white. It’s more like white/watt, like wattage, like electric.

Audience Member 1: That’s awesome. I was actually reading that book on the BART train on the way over here and the language is so resonant. It’s just very, very powerful. I’m wondering, what are your feelings about that early writing now? Do you ever go back and look at it?

Patti Smith: Some of it I still really like. I think you can’t really judge work you did when you’re young. I was in my early twenties when I wrote that book. Sometimes I’m amazed at some of the things I did when I was young and sometimes I can see how indulgent some of it is, and I really would like to edit some of it. But on the whole, the one thing that comes through always to me is that I was always working. I’ve always done, no matter how bad, like, if you think I sung bad or I’m too nasally or whatever, it doesn’t matter. In my life, I have always tried to do the best that I know how to do. And that’s about it.

City Arts & Lectures: This question is from the center of the balcony.

Audience Member 2: Hi, Patti. I wanted to ask about your decision to cover “When Doves Cry” by Prince. I was also wondering if you had anything you could share with us about your feelings about his contribution to music.

Patti Smith: I covered that song because I really like it, and we still do it. I’m not really the one to talk to about Prince, because he wasn’t one of my favorite people. I mean, I wasn’t really into Prince. I just really love that song. You’d have to ask somebody else about Prince. I don’t have anything against him, he’s just like, not my thing. I’m not going to stand here and say “the rich legacy that Prince…”. We all know that he was very prolific and gave us a lot of great work. I just wasn’t into him.

I actually am into Fleet Foxes. I don’t know why I said that, except I really do like them. Do you know that you can get a channel? Somebody showed me how to do it, and then I could never find it again. There’s some kind of channel on the radio where it’s all Fleet Foxes all the time.

Dan Stone: They have enough music for that?

Patti Smith: I mean, some things come on again and again, but I could listen to “Your Protector” a million times.

City Arts & Lectures: This question is all the way at your right at the back of the orchestra.

Audience Member 3: Hi, Patti. I’ve always loved you, and I always will. I have a question, it has to do with you mentioning W. Sebald in your book. It’s the first time I’d met anyone who really loved him. And I just feel that a lot of your writing is so much like his and the photographs, and I’m just wondering if he influenced you a lot.

Patti Smith: I don’t feel so influenced by him, I just love him. I love looking at his books. One of the reasons I love them is because they reminded me of Breton’s Nadja. That book actually really influenced me because I was very young when I saw it, and it has all these photographs, a lot by Man Ray. That book was a big influence on me. Most of Sebald’s books I admire, but they really didn’t put me on any specific path except for his book poetry called After Nature. That book really resonated with me, I read that over and over and it has no photographs in it. It’s almost like imagined historical poetry. I would recommend that book to anybody, great loss that we lost him.

City Arts & Lectures: This question’s from the balcony to your left.

Audience Member 4: Hello. You’ve spent much of your time and your adventures in devotional travel and pilgrimage, visiting graves. I was wondering after you’ve grown up and had your brown bread coffee shop, what you’d like us to bring you when you have a grave of your own?

Patti Smith: That’s not a bad question. I like those little blue flowers called cornflowers and I like eucalyptus. I don’t want a bunch of plastic junk and stuff like that, or letters or candles, or half-drunken Coca-Cola cans or anything. Just come and hang out and take a picture if you want. But it’s not such a bad question. I actually have thought about that. What do I want my grave to look like so people can come and feel comfortable? Maybe a little stone bench or something like that.

I like to visit people’s graves. It’s nice to be in the proximity of people that have given us a lot. Could be our mother or our brother, but it also could be our favorite poet or a beloved teacher. I find it a very comforting thing, and also it gives us a moment, a quiet moment to meditate on the work of these people, or all the hard work of one’s parents or whatever our thoughts. And sometimes you go to a grave, you don’t feel anything. You should never go to a grave and feel like you’re supposed to either cry or have a mystical experience. I’ve gone across the sea to a grave and just couldn’t wait to leave. You never know what you’re going to feel, you know? In any of these things, you just have to be yourself wherever you go. So if you come and visit me, just be yourself and clean up your mess before you leave.

No one wants to follow that one.

Audience Member 5: Hi, Patti. Thank you so much for your songs, it’s always a pleasure to hear you in performance. I love your version of Bob Dylan’s “Wicked Messenger,” and I know you’re a big fan. Two-part question: can you tell us a story about how his writing reached you, and also an interaction with the man himself. You’ve performed with him, on the same bill with him, I believe? Maybe?

Patti Smith: The first question would take too long to talk about, but I can tell you a nice little story about the second. After my husband died, Allen Ginsberg had talked to Bob and said, you know, Patti’s sort of in a rough spot, maybe you could help her get back on her feet. So Bob had us go on an east coast tour with him. It was my first tour since 1979, and this was 1995, I think. We would go on before Bob, and about the second or third day, he asked to see me down in the basement. I had my hoodie and I go down there, and he’s got his hoodie and he goes down there, and he says [imitating] “Uh, Patti, um.” He had his lyric book and he said I could pick out any song in the lyric book and we’d do it together. All night long I went through this lyric book and I’m thinking, I’ll do “Highway 61” and I’ll be really cool. Do it in sort of a mean Elvis way. Then maybe, no, I’ll do this one, or we’ll do that one. I went through like, 9 million songs and then I thought, well, he’s a guy, I’m a girl. I decided to take a different route because it would be expected that I would try to do something more aggressive. So I picked the song “Dark Eyes,” which is so beautiful. Not one of his more popular songs, but has very Blakean lyrics, such a beautiful song.

I picked that one and he said, [imitating] “Oh, ‘Dark Eyes,’ uh.” Anyway, we did “Dark Eyes” for the next eight or nine jobs. I always just dress in a t-shirt and dungarees or something, and I wanted to look nice. Michael Stipe was traveling with us because I was so nervous and he was the cheerleader guy, keeping my energy up. So he took me out and bought me a dress. It looked like an old pioneer dress except it cost a lot of money. So I put it on and took my shoes off and went out on stage and sang “Dark Eyes” with Bob. I have to say it was, night after night, some of the happiest moments on stage I ever had, because I really always loved him. We used the same microphone and our noses were this close and it was so hot, the lights, and our sweat would come down and merge and go ping!

If you go to the YouTube and if you look up “Dark Eyes,” somebody I think took it with a phone or something and it’s a little jiggly, but it’s really nice. If you want to see it.

Dan Stone: How about some songs now? That sound good? Bring this stuff out. Patti, it was really nice talking to you. It was a real pleasure. Is Lenny a coffee drinker?

Patti Smith: No. So this is Lenny Kaye.

[Sings “Wing” by Patti Smith]

Thank you. Tomorrow, Lenny and I will be attending and participating in a memorial for our great friend, Sandy Perlman. For those of you who didn’t know Sandy, we met him about 45 years ago. Sandy was one of our great rock journalists. He helped form the most poetic and abstract and intelligent aspects of rock journalism.

He was the first person who ever told me that I should sing rock and roll and get a rock and roll band. And I thought he was crazy, but to prove he wasn’t crazy, he offered me to sing with Blue Ӧyster Cult, who he produced and wrote many of their pivotal songs. He also produced The Clash and he gave many contributions to the formation of digital downloading and recording.

But the best thing about him is he just had a beautiful mind. You could talk about everything from Shakespeare to Benjamin Britten to heavy metal. In fact, he taught a course in Montreal on the correlation between Metallica ballads and Benjamin Britten. Sandy had a beautiful mind. He was a great friend and we salute him and we’d like to do a little song in memory of him.

[Sings “Beneath the Southern Cross” by Patti Smith]

Thank you. Tomorrow, Bruce will be here—Bruce Springsteen, that is—and we wish him all the best on his new book. So to get this stage ready for him, just thought I’d do a little song.

[Sings “Because the Night” by Patti Smith Group]

[Sings “People Have the Power” by Patti Smith & Lenny Kaye]

Don’t forget it: use your voice! Vote! Vote!

[Gestures toward Lenny] Lenny Kaye. Thank you, everybody. I had a great time.