Ryan Bauer: Good evening. I’m Ryan Bauer. I’m a rabbi at Congregation Emanu-El in San Francisco.

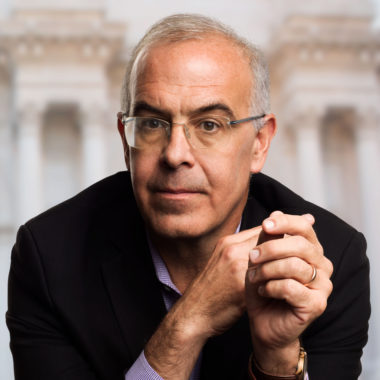

I would like to welcome you all to the Sydney Goldstein Theater. It’s an incredible space. So tonight we’re joined by David Brooks. The author of “Bobos in Paradise,” “The Social Animal,” “The Road to Character.”

But tonight we’re here to talk about his new book, “The Second Mountain.” This work is radically different than anything he’s done before. Throughout his career he’s been a commentator looking back on our society, on our politics with a strikingly new lens. But here in this book, he’s actually turned that camera around, and he’s flipped from the outside to one within, where we learn about David’s internal world.

So please give an incredibly warm welcome as we welcome David Brooks.

David Brooks: Thank you. Never heard a cheer for a rabbi just, you’re like the rock and roll rabbi of San Francisco.

Ryan Bauer: Should come to San Francisco more often.

David Brooks: Yeah.

Ryan Bauer: They love their rabbis.

So this is a deeply personal book. And the first thing was, I just want to thank you just for being so vulnerable and open and just sharing yourself with us, because you don’t see it that often. Because it feels like your last three books–it was more than that, but really the last, I think about “Bobos in Paradise,” which is really, you know, it’s like a satellite kind of looking at society. And then we move to the “The Social Animal” which starts using neuroscience, like you know, how do we work inside? And then we move to “Road to Character” and you’re looking at our values about you know, what are resume virtues versus my eulogy virtues? But this went into deeply personal.

And the more I thought about it, I realize we probably shouldn’t start here on “The Second Mountain.” It seems like a 50 year journey which actually got to right here. And so I want to go back to the beginning. And if you could just tell us about your childhood. What influenced you growing up?

David Brooks: Well, I was conceived in February of ninteen sixty… I grew up in New York in Greenwich Village more or less and my parents were professors. And the story, two stories I tell about my childhood, which are somewhat symptomatic…

We were somewhat left wing. And in the late 60s my parents took me to a be-in in Central Park, where hippies would go just to be. And one of the things they did, they set the garbage can on fire and threw their wallets into it to demonstrate their liberation from money and material things. And I was five and I saw a five dollar bill on fire in the garbage can, so I grabbed the money and ran away. So I say that was my first step over to the right.

Ryan Bauer: So you blended really well, is what you’re saying.

David Brooks: I blended… So I was like a hippie kid. I got paddled in second grade, and I feel bad about this actually. I wrote “Julie Nixon is a Nazi” on the board. And I don’t know why I picked on Julie Nixon, but there it was.

And then the other thing was I discovered at age seven I wanted to be a writer. I read “Paddington the Bear” and at that moment I decided this is what I’m going to do. And my joke–in high school I dated a woman, I wanted to date a woman named Bernice, and she dated some other guy. I remember thinking “what is she thinking, I write way better than that guy?”

And so, so but I had more or less an extremely happy childhood, the kind that nobody has anymore. Because at at age seven I had free reign of New York. And you could go wherever you wanted. Although, I went back about a year ago and read “Paddington the Bear” again, and I was shocked by it, because it’s a very sad book.

Ryan Bauer: Yeah, it is a sad book.

David Brooks: It’s about a bear that comes from Peru and is lost in the train station with nobody to love him. And then gets taken in.

I thought well really, what was going on in my life that caused that to appeal to me? So. Yeah.

Ryan Bauer: Because I think the author says that you know, he was influenced by the train station in London during World War II when children had their tags around their necks.

David Brooks: I didn’t know that.

Ryan Bauer: Yeah, that’s what Paddington is. Why do you think you were drawn to that?

David Brooks: I wonder if I was secretly emotionally lonely. I came from–there are two kinds of families in Jewish New York. There’s the hugging warm kind of family and then there’s the reticent family. So I grew up in the second tradition.

There was a certain kind of Jewish family that their way of assimilating was to ape Anglican stuff. Victorian England. Yeah, so they gave all their kids–the phrase was “think yiddish, act British.” And so they gave all their kids names, English names so nobody would ever think they were Jewish. And they were names like Sidney, Milton, Norman, Lionel. And within like five years they were Jewish names.

Ryan Bauer: Oh those are Jewish names.

David Brooks: Yeah. So it didn’t work. But you know, we had the immigrant–if you start at 14th Street and moved South for about a mile or half a mile, you pass my great-grandfather’s kosher butcher shop, where my grandfather practiced law, where my mom and dad grew up, where I went to elementary school, and where my son is now in college. So that’s five generations rooted in one spot.

And we were raised with that immigrant mentality. We’re strangers here and we got to make it in the city. And by the city we meant like north of 59th Street where Protestants lived. And you know, they’re tall slender people who don’t have thighs. They just have one calf on top of the other. So we wanted those–that’s what we wanted to be.

The final thing to be said, and I’ve never told this story in public before, but I was very much raised by my grandfather. My mother’s father. Who worked in a law firm, but he was really a writer. And he wrote. And we’re not in a family that hugged, we never said we loved each other. But he really poured love into me through taking me out to Child’s Pancake House and some of the delis on the Lower East Side.

And actually it’s in the book, but it’s–nobody’s ever asked me about it, it’s one of the most shameful moments of my life. When I was like 22, he was dying in the hospital and I walked into his hotel room to visit him and he said “I’m a dead duck. I’m long here.” And on the way out–I sat with him for a few hours–and then the way out he said “God, I love you.”

So. And no one in my family had ever said that to me. And I emotionally froze up and instead of turning and saying “I love you, too,” I sort of acknowledged it, but I didn’t utter the words I should have uttered. And so that’s you know, one of the things that happens when you grow up in an emotionally reticent family. You feel the emotions and the emotions are in the background, but you don’t have the capacity to express them.

Ryan Bauer: When did you first start expressing them?

David Brooks: I gradually over–well when the kids are born then you become aware of a level of love and commitment that you didn’t know existed before. And so my kids and I are very physical. We play sports together and stuff like that. So my mother once asked me, “did you raise your kids the exact opposite way?” And not consciously, but definitely we’re much more physical with the kids.

Like the story I tell about about that is when my oldest son was born we were in Brussels, and he came out with a super low Apgar score, and so you don’t know what’s happening. He gets whisked off to intensive care, and before he was born, and I remember thinking “suppose he dies in 30 minutes of life. Would that be worth it for his mother and I had to have a lifetime of grief?”

And if you had asked me that before he was born I would have said “no way it doesn’t make any sense.” But after he was born you become aware of it, that of course his life is of infinite value. Of course, it would be a lifetime worth grief.

Ryan Bauer: Did you express that to him in words? Like you didn’t in the hospital?

David Brooks: Well he was only a day old.

Ryan Bauer: Okay. At had a few years old?

David Brooks: Yeah, he I wouldn’t say it because yeah, we–it’s with different kids, you’re different parents. Yeah, and so with my daughter we end every call, “I love you. I love you.” With the boys it’s a little less of that I guess. But I think it’s, I think we have a pretty warm close relationship. So I would say… But I should say it more.

But once you get in the habit, and this was true in the old years in my family. Once you get in the habit of not saying it, it’s super hard then to say it. You’re locked into some pattern, of family pattern, and you can’t get out. And so I’m aware of that. My mom died about two years ago, and I’m aware that we never got out of that that pattern.

Ryan Bauer: Call them after this.

David Brooks: I should, believe me.

Ryan Bauer: So, University of Chicago. How did you choose that?

David Brooks: Well the admissions officers at Columbia, Wesleyan, and Brown decided I should go to the University of Chicago.

So I applied to four schools, I got into one. So choice is not the operative verb there. And what’d I say about it is it’s, the old saying is “it’s where fun goes to die.” The best saying about it is “it’s a Baptist School where atheist professors teach Jewish students St. Thomas Aquinas.”

Ryan Bauer: But you’re effusive. I mean what you write about it in this book, I’m assuming you either work for the development department at University of Chicago, or they’re going to call you really soon.

David Brooks: Yeah. I don’t know if other people feel this but I feel more affected by my college now than I did the day I graduated. So Chicago, when I was there, had some of the old refugees World War II and they had the fever that if we read these great books–Kant, Hegel, Plato, Aristotle–that the secrets of life were in these books. And so they just communicated that intensity.

There’s a phrase “if you burn with enthusiasm people will come for miles to watch you burn.” And we just came and we were caught up in this fervor. And they did a number of things for us. The first thing they did was they taught us to see. And you think seeing is obvious, you look out and see. But I work in politics, people don’t see the world accurately. They see what they want to see.

And John Ruskin, the Victorian art critic once said, “The more I live, the more I think it’s important, the most importance I think there is, is to see something and then write what you saw with a plain style. That a thousand people can talk for one who can think, but a million can think for one who can see.”

And so when you read Tolstoy you’re seeing with a clarity that you did not know was capable. So there’s a scene in Anna Karenina where Kitty, a young woman, is going to the ball and she’s the belle of the ball. And Tolstoy describes what it feels like to put on the gown and it fits perfectly. She’s got a velvet choker, it feels perfect. Her hair is perfect.

So he’s a middle-aged guy writing, but he describes what it feels like to be young woman at the fullness of life feeling perfect. And then she goes to the ball and everyone’s staring at her and she’s dancing with all the different men and there’s one man, Vronsky, she thinks is going to ask her to the last dance and ask her to marry her on the floor.

And she’s filled with enthusiasm for this. And she sees Vronsky while she’s dancing with another man, and he’s looking with the look of look of adoring love. She sees him again. He has that look of love. It’s not for her. It’s for somebody else. Anna Karenina. And Tolstoy describes what it feels like to have her whole soul and inside sucked in. And when you see reality with that clarity, you have a model.

And then the other thing I think schools should do is give us new things to love, and to reorder desires. Tell us what is the highest thing worth loving. And after you’ve read Kant or Hegel or whatever, you’ve tasted the pure wine and it’s hard to be satisfied with Kool-Aid. And so you’ve touched the high standard.

And then the final thing Chicago did was they didn’t tell us what to think, but they said “listen there are moral traditions in this world. There’s the Roman tradition that honors honor and glory. There’s the rationalist tradition about science. There’s Buddhism, whatever. All these moral traditions that have been handed down to us. Pick one.”

And so just being acquainted with those moral systems gave us categories in which to think. And sometimes–and I’ve learned this teaching. Sometimes you pour into a class more than your students are ready to receive. Because they’re 21. But if you plant the seeds correctly, then when life starts happening to them they have the resources to go back and say “oh that’s what that was all about.” And I would say that’s happened repeatedly to me in the course of my life.

Ryan Bauer: So when, you know, when you talk about how these professors they poured into you. You know and they filled you up in these philosophers and Western Civilization, and the way it changed you and helps you see, what advice would you have for us or what philosopher should we look at in this moment of total chaos in our country?

David Brooks: That’s a good question. I mean the philosopher that changed my life was Edmund Burke. And I came in as a Bernie socialist and I was a socialist all through college. Pre Bernie. He actually went to Chicago too, coincidentally. But I read Edmund Burke and he’s a guy who says, “you know, don’t think to yourself, don’t put too much faith in reason. Put your trust in tradition. And the way things have stood the test of time.” And I thought “this is awful. I want to think for myself. I want to have a revolution.”

But then I got out, and I was a police reporter and I covered something called Cabrini-Green on the Robert Taylor Homes, these housing projects. And they were well intentioned social programs to improve the lives of the least fortunate. And they tore down old neighborhoods that seemed rickety and they put up these brick high-rises. When they tore down the neighborhoods, they not only tore down the buildings, they tore down the social capital, the arrangements people had to help each other out. And when they put them back in the towers, it didn’t come back. And so their lives were materially better, but spiritually and socially worse.

And the towers became awful places, almost uninhabitable, pretty soon. And so I looked at this and I said “that’s what Burke was talking about. Be careful how much you can know and be suspicious of the power of reason. And trust in what he called our ‘just intuitions’ and the moral traditions that have been handed down to us.”

Ryan Bauer: I mean, is that saying when we’re breaking so much of society, that it’s going to have effects that we can’t comprehend?

David Brooks: Yeah, the things that connect us are largely invisible. And there are things that enter us throughout the centuries that we’re scarcely aware of. And so for example, just one quick political example, many years ago, Joe Lieberman in Connecticut ran against Ned Lamont.

And in the 16th century, Connecticut had two sorts of settlements: Portuguese towns and English towns. This is in the 16th and 17th centuries. Ned Lamont won every Portuguese town. And Joe Lieberman won every English town 400 years later. There are a number of great books about the settlement of America from different parts of England. And how those settlement patterns have remained consistent across time. We are the bearers of historical traditions that we are not even aware of.

Ryan Bauer: So when do you–so post-college, when do you realize that you want to become a writer? When does that become your vocation? Because you put a real emphasis in this book on vocation.

David Brooks: Yeah, I well. I knew I wanted to be some kind of writer at age seven as I say, and literally a day is not gone by, maybe 200 days in 50 years that I haven’t written.

Ryan Bauer: And it really is spurred by Paddington.

David Brooks: Yeah, and I…

Ryan Bauer: Which is ironic because Paddington, as you said, it is a book about loneliness.

David Brooks: Yeah.

Ryan Bauer: And then here we are, you know, fifty-three years later, saying the world’s lonely.

David Brooks: The thing about writing is first of all, it tends to to attract aloof personality types. I tell journalism students, if you’re at a football game and everybody else is doing the wave and you don’t do the wave, you have the right kind of aloof personality type to be a writer.

And I have a friend, a poet at Yale, named Christian Wiman. He says one of the reasons we go into poetry or writing or art or music is we don’t connect naturally at a party, we’re not convivial. The only way we can connect is through our work. And so he says a certain emotional reserve is a source of great power in your work. And there’s a line from Garry Shandling, whatever his name was, that “my friends say I have an intimacy problem, but they don’t really know me.”

And so you start out with a sort of aloof style and a detached observer style and then you are in a profession that involves a lot of solitude. And so John Cheever is a novelist who lived in New York and he got up every morning, he put on a suit and tie, he rode the elevator down to the basement of his building where he had an office, he took off the suit and tie, and he wrote in his boxers, and then at 12:30 he put on the suit and tie and he rode upstairs and made himself lunch. Like that’s the life. And so the life is a lot of aloneness.

And then the weird thing I found is when I achieved commercial success, it was lonelier still. Like I have–my last book did well, I was on a book tour for like 99 days, and I counted at one point in the middle of that, 42 consecutive meals that I ate alone, either at an airport, airplane, or hotel. And when you do that, it’s amazing how you lose your bearings. And I remember in the course of that time, I saw a photo, Britney Spears sort of went crazy and shaved off all her hair. And I was like, “yeah, I could do that.”

Ryan Bauer: I already did that.

David Brooks: Yeah you did that.

So writing is– you get sentenced to be a writer, but you miss the connection you longed for.

Ryan Bauer: But you’re also, you’re drawn to it at the same time–I mean that’s you know, one of things you write about is that you wear this Fitbit. And you know, in the morning it thinks you’re sleeping, because when you’re writing alone it is David’s happy place.

So I guess my question is–there’s where your Fitbit thinks you’re completely at peace, which is when you’re solitary and alone. There’s the public David, which is you know here, on PBS NewsHour. And then there’s also the David in relationship. How are those different?

David Brooks: Well, I hope they’re not too different. But there’s a quiet, like the episode, I put on a Fitbit in an attempt to lose weight. A failed attempt. And…

Ryan Bauer: You should put on two next time.

David Brooks: Two fitbits. One set at a slightly higher reading.

Ryan Bauer: Yeah.

David Brooks: And it was telling me on my screen that I was sleeping every morning between 9:00 and 11:00. I was like, I know I’m not sleeping. That’s when I’m writing. And so my apparently my heart rate goes down or something. I don’t know, but I will say, and even writing this book, it got me thinking, it look forced me to think about things that really matter.

And the way I write is not typing. I take masses of pages of information that I’ve xeroxed or written out and I arrange them on piles on the floor. And each pile is a paragraph in what I’m writing that day.

And so I’ll have 20 or 30 paragraphs on the floor on my carpet. And my writing process is really crawling around the carpet organizing my piles. And when the creative juices are flowing and I’m writing out Post-it notes, that’s magic time for me. And that’s the most fun part about my job.

And the person I am on TV–it’s actually, that’s a pretty natural me, I think, you can’t fake it on TV I’ve learned. And especially the–I do with Mark Shields. And what Mark is on TV, that’s Mark. He is just a very loyal, very warm Boston South Irish guy. And our relationship is excellent. And it’s just who we are and we’ve been doing it so long we don’t feel like we’re on TV. We’re just talking.

Ryan Bauer: So, how did you come to write this book?

David Brooks: Well, it started out frankly as a book on commitment making because I felt that the core problem in society was hyper-individualism. And we’ve gone through, we went through a period in the 50s where we had a culture that was very communal, where the culture is really we’re all in this together. We’ve got to get through the Depression. We got to get through World War II. Big organizations, we’re all in this communal…

And then in the 60s we sort of chopped that up and we had a very individualistic culture in this city and in New York that started. I’m free to be myself. And we’ve run out of–we’ve done 60 years of hyper-individualism and it’s liberated a lot of energy and made life a lot more fair and the food more interesting.

But we’ve weakened the attachments between us. And so we live now in a society that’s isolated and detached. And so the suicide rate has gone up 30%, the teenage suicides since 2011 has gone up 70%. 72,000 people die of opiate addiction every year. It’s all about detachment, social isolation. Some detached lonely guy’s going to shoot up a synagogue, because some guy in a basement reads hate. And wants to pretend his life has significance.

And so all of my columns were really about detachment. And I thought the answer–we’re not going to go back to deference to authority. We have to learn how to commit to each other. And so I wrote the book about that and then in the middle of the book, I realized what we writers do is we work out our stuff in public.

And I realized at some level–it was partly about our national detachment, it was also partly about my personal detachment. And so I was in the valley, and we’re now in a national valley, and how do you get out of the valley? And eventually I was persuaded that my personal story was connected to the national story. It’s a similar process that a lot of us are going through at once. And so how do you get out of a social valley?

Ryan Bauer: So I’m going to ask you to actually read a section here. If you could just read right here on page 48 for us.

David Brooks: It is a reasonably long section, so patience.

The odd thing about the soul is that while it is powerful and resilient, it is also reclusive. You can go years without really feeling the force of its yearning. You’re enjoying the pleasures of life, building your career. It’s amazing how untroubled you can be, year after year, while your soul is out there somewhere far away. But eventually it hunts you down.

In this way the soul is like a reclusive leopard living high in the mountain forest somewhere. You may forget about it for long stretches. You’re busy with the normal mundane activities of life and the leopard is up in the mountains, but from time to time, just out of the corner of your eye, you glimpse the leopard just off in the distance, trailing you through the tree trunks.

Ryan Bauer: So tell–what do you mean by that? What do you mean by that, and also, when do you feel like your soul was hunted down?

David Brooks: Yeah. Well, I think first I want to establish that we have souls. And so I want us all to believe that, whether you believe in God or don’t believe in God, that there’s some piece of you that has no size, weight, color, or shape, but it gives you infinite value and dignity. And that rich people don’t have more of this than poorer people. And that slavery is not just an attack on a bunch of physical molecules, rape is not just an assault on a bunch of physical molecules, they’re an attempt to obliterate another person’s soul.

And so to me what the soul does first, it gives us our fundamental equality. Our brains are not all equal. Our bodies are not all equal. But our souls are equal and infinite.

The second thing is it does is it gives us moral responsibility. A tiger’s not morally responsible. But a human being is morally responsible for what he or she does.

And the third thing it does is it yearns. It’s a source of desire. It’s a yearning for righteousness. And I think implanted into us is a desire to lead a moral and meaningful life.

There’s a great passage in “East of Eden,” I think I quote in there, from Steinbeck, where he says, “a moral drama is the ultimate only story we know. At the end of your life when all the chips have fallen, there’s only the same clean question. Did you live well, or did you live ill? Was it good or was it evil?” And so…

Ryan Bauer: Is the evil when it’s hiding?

David Brooks: Excuse me?

Ryan Bauer: Is the evil when the soul is hiding, like that level?

David Brooks: Well I think you can numb the soul. And you can live a life where you’re thinking about your next job or your next achievement and you turn off the moral lens.

And I tell the story in there of a group of an Israeli daycare center where the parents were coming late, and so they imposed fines on the parents when they came late, and the amount of parents who came late doubled.

And that’s because they saw it not as a moral responsibility to the teachers, but as an economic transaction. Not through a moral lens, but an economic lens. And you can do that as a society. You can morally distance and turn off the moral lens. And the yearnings of the soul get covered over by the yearnings of the ego and the yearnings for material success, the yearnings for career success, but I think there are times when the soul wakes you up. When you’ve shrunk your soul it pounces.

And so there are times in the middle of the night when you wake up and there’re nights we all have where it’s a bad night, you have bad thoughts. Anxieties pulsing through your head. A friend of mine said you have nights when your thoughts come to you like a drawer full of knives. And your soul is sick then.

And then I think there’s a moment, probably inevitable in everybody’s life at some point, where the leopard comes out of the forest and sits on the floor in front of you and asks for your justification. What are you here for? What are you doing? What good are you serving? Why were you called? And there you either have an answer or you don’t have an answer.

And I think a lot of people–and in my case, I achieved way more career success than I ever thought I would, but I wasn’t sure I had an answer to that. And I would say among my students, we’ve given them no help about how to even think about the question. We’ve spent so much time training them to be achieveatrons that they have not been given the moral vocabulary or the categories to think about the question.

And if you don’t have a concept of redemption, of sin, of forgiveness, you don’t know how all that stuff works, how the soul gets sanctified or degraded, then it’s hard to even articulate what’s going on. It emerges as a sort of vague and amorphous hunger that you don’t quite know how to satisfy.

Ryan Bauer: I’m going to ask you to read. I like when you read. I’ll have you read one more passage here.

David Brooks: Can’t you find somebody else’s book?

Ryan Bauer: I was looking for someone else up on the stage here, but what are you gonna do? So if you could just read this right here.

David Brooks: Okay that highlighted part.

The knowledge that we acquire through suffering can be articulated, but it can’t really be understood by someone who did not endure the path it took to get there.

I will say I did not come out of that pit with empty hands. Life had to beat me up a bit before I was tender enough to be touched. It had to break me a bit before I could be broken open. Suffering opened up the deepest sources of the self and exposed fresh soil for new growth.

Ryan Bauer: So what happened–tell us about that part in your life. When that pain…

David Brooks: Yeah I had a part in 2013 who–my marriage had ended, my kids had left for school, and I was living in an apartment in DC. And I had weekday friends people I could take out and talk politics with, but didn’t have weekend friends, like real friends.

And my life had been so organized around writing. A few bad things had happened. One I cared about reputation, where I ranked, but more numbingly, I valued time over people. I had all these deadlines that I was always having to meet and so I was on the move. And people sensed I think, a closedness. And so I was not the sort of person people confided in me.

And so, you know, the wages of sin are sin. You’re stuck there in an apartment with these long empty weekends, that are just going to be silent. And that days I was in great shape. I would go on these eight mile runs just to fill the time. And if you opened the door, I wasn’t entertaining, if you opened the door to my kitchen, where there should have been silverware there were post-it notes, and where there should have been plates or other utensils there were pens and envelopes and stationary, because work is a seductive way to avoid a emotional and spiritual problem. And so it was a moment you get broken open.

And I learned a couple things in the valley there. The first is that freedom sucks. My friends were projecting all their fantasies on me. Unattached, I could do whatever I want. It sucked. That political freedom is good and economic freedom’s pretty good. But social freedom is bad. And we tell our students, “oh be free, keep your options open.” Terrible advice. Freedom is not something you want to swim in, it’s a river you want to swim across so you can plant yourself somewhere on the other side.

And the second thing I learned is that you can either be broken or you can be broken open. And some people get broken by times of tragedy, they shrivel up and they close in on themselves, and they get resentful and angry about the world, and they lash out, they cause pain to people around them. There’s a phrase I like, I forget where I read it, “pain that is not transformed gets transmitted.”

And there’s a lot of tribalism in our society. And those are people who’ve been broken by hurt. But then you can be broken open, and I quote this Theologian Paul Tillich from the 1950s, who says that what seasons of suffering do is they interrupt your life and they remind you you’re not the person you thought you were. They carve through what you thought was the basement of your soul and they reveal a cavity below, and they carve through that, and reveal a cavity below. You get introduced to hidden depths of yourself, and you realize that only spiritual and emotional food is going to fill those depths. The desires of the ego are not going to fill those depths.

Ryan Bauer: So when you’re in that cavity and you’re in the bottom and you’re in that valley, what pulled you out?

David Brooks: A lot of sad Irish songs.

Well, I’d say what pulled me out, there were two things that I’ll mention. One is there is a community I got embraced by, I got introduced to a community. There’s a couple named Cathy and David in DC who had a kid in the DC public schools. And they had a kid who had a friend named James who didn’t have a place to stay or live or eat, so they said “well James can stay with us sometimes.” And then James had a friend and that kid had a friend.

And I walk in there, I get invited over for dinner, and I walk into the house, and there are 40 kids around the table and 15 sleeping around the house. And I walk in and introduce myself to a kid and he says “we don’t really shake hands here. We just hug here. ” And I’m not the huggiest guy on the face of the Earth, but I’ve been hugging with them since.

And what those kids had was they had this total unwillingness to tolerate social distance. If you were going to be in their presence, you were going to show emotionally all the way up and they were going to show up emotionally for you. And that was an introduction to a different way of living. A way of living where emotional transparency with a thing. And I would go there, I’d write about social isolation in the day, and then I would go to these Thursday night dinners, and realize this is the answer.

And then later…

Ryan Bauer: Do you consider that your community?

David Brooks: Yeah. I mean it’s a second family. I have my family but they’re a second family too.

Ryan Bauer: Is that hard when you’re in different phases of life and you know, given continuity, you know, this kid here is kind of moving through the program and then…

David Brooks: No it’s not. I’m a 57 year old white guy, most of them are 17 year old black kids. On one level we don’t have a lot of common, on another level we have a lot in common. And we’ve gotten to know each other… I mean, you know when I think about them…My name is David, you know Ryan– we have names that are like white people names. And their names are Azari, Kaliko, their names are, they’re different kinds of names.

But we go around the table and a lot of them tend to be artistic, they’re musicians, they’re videographers, are DJs, and just we share what we had that week, whether it was a good thing or whether it’s a bad thing. Whether it was depression or whether it was passing the GED exam.

One of the young women in the community, her kidney failed, so David, the father figure in the community, gave her a kidney. And so it’s funny, we’re different if to look at us, but we’re very close now. And it’s been an answer to how you really can create community across differences.

Ryan Bauer: When did you realize that you weren’t alone in that apartment anymore? That you’re…

David Brooks: Well I began to, a constellation of friends, and constellation of warm places. And then the woman who would become my wife, who’s in the room tonight, entered life and love has this way of filling up those places. And giving and receiving love. And you know, when you’re, the hard part about being in the valley is sometimes you have bad moments. My mom died a year and a half ago and that, you know, that’s a valley.

But this, in 2013, it was a valley caused by myself. And it was a valley that was caused by an awareness of a spiritual void in myself. And a relational void. And so that’s a different kind of valley. Because that kind of valley is a foghorn. The pain is an announcement that you’ve done something wrong, that the values here are wrong.

And I think that’s true, by the way, of the of the nation. That our values are wrong. And we’re in the valley caused by the embrace of wrong values. And so you get out of that–and it’s funny, it’s both a spiritual process and an emotional process. And I’m struck by how the heart and soul often work in tandem. And how learning to be open with a person, learning to love a person, accepting love, which is not an easy thing, and being willing to receive love is–these are both spiritual and emotional experiences.

Ryan Bauer: So that’s the relational. What about the spiritual? How did you come out of the spiritual valley?

David Brooks: I read a lot. I mean, I read a lot of books. And some of them were Jewish, Avivah Zornberg, became a fan, I don’t know if you’ve read her. She’s a brilliant writer on–she wrote an amazing book on Exodus called “Particulars of Rapture.”

I read CS Lewis, I read Henry Nouwen, and I read Reinhold Niebuhr. I read Abraham Joshua Heschel, Martin Buber. I found it very useful to have a spiritual book going all the time, because if you’re not aware of how your soul gets enlarged or shrunk, or you’re not aware of a transcendent object that your skull is aiming for, then you’re cut off.

Ryan Bauer: So in the book, you know, you talk about, you call yourself a Wandering Jew, and a confused Christian. And most people I know in the communities, they think of those as totally distinct communities. You’re either in the Jewish Community, or in the Christian Community. Explain to me where you are.

David Brooks: Yeah. Well, I grew up in both communities. So they don’t feel that divorced for me. So I grew up in a very Jewish home. My grandfather took me to shul. We were secular Jews I guess, but I had a bar mitzvah and we were and I am a Jew. I’m of the Jewish people. And my sensibility is Jewish. My life is Jewish. My friends are all Jewish. We’re ironic together all day long. And so that is–and my grandfather who I talked about was, the Jewish people was a strong force in his life. And Israel is a strong force in my life.

But I also went to something called Grace Church school, an Episcopal School, and for 15 years I went to an Episcopal camp. That place was really the core of my childhood. And so I grew up around Christianity as well. We sang in the choir and because it was New York, the choir was about 25 percent Jewish. So we sang the hymns and didn’t sing the word Jesus to square it with our religion. So the volume would drop down and then come back up.

And so I lived at these two moral systems together. And then through college I was a big admirer of Reinhold Niebuhr and also Saul Bellow. And so I had these two systems in my life and it wasn’t confusing because I didn’t believe in God, so it’s just like two moral traditions, oh that’s fine.

And then gradually, slowly, and incrementally, I came to believe that there–I had, the way I would put it is, two ways of putting it. One is, my experience of reality had a wider amplitude than the categories I had in my head for understanding it. And so a faith that was latent in me came out. And basically once you see that human beings have souls, and that it’s probably a joint soul at some level, then you think that we are not just in a material existence. That there’s a created order. And that God, and my favorite formulation of God, is God is the ground of being. The basic animating force of love in the universe is a divine presence.

And so I came to see that just–and I couldn’t understand the stories I was telling as a journalist without a sense there was an ultimate meaning. And I couldn’t understand the sense that there is a such thing as right and wrong.

One of the stories I tell in the book is about Tolstoy, who had a great first mountain. “War and Peace” and “Anna Karenina” are pretty good. But he went to see his, he lost his brother who died young and he couldn’t understand why his brother lived or died. And then he went to Paris and he watched what they had in those days, a public execution. And he said, “as I saw the head and the body fall into the baskets, I knew that this was wrong. And I knew it was wrong not because of some theory people had, but because it was eternally and always wrong, and I came to see that undergirding the ground of the universe is such a thing as eternal truth. And that eternal truth is not devised by theories, but is somewhere embedded in the structure of the universe.”

And he went into a crisis. He took away guns and he took away any ropes because he thought he’d kill himself, because his whole life had been chasing the approval of other people. And he realized that didn’t matter, what mattered was some transcendent eternal truth, which can’t be introduced by or approached by reason and can only be approached by prayer. And so he said “I have to find some other way of approaching truth, which is more down here than up here.”

Ryan Bauer: So. I’m still trying to understand this. For you, your signifier as Jew. Is it ethnic? Is it religious? Is it cultural? Are you part of the nation of Israel? How do you identify? What does that signifier mean to you?

David Brooks: And this answer won’t satisfy you because you’re wearing a kippah. So I’m just taking that as subtle…

Ryan Bauer: Does that give it away?

David Brooks: So now I feel more Jewish than I ever did in my life. Because I’m not only part of the Jewish people, I think the story of Exodus is a foundationally true story about human existence. And so I think there really was a God who talked to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

But in the course of my life, I grew up in this Christian tradition too, and as I say in the book, I can’t unread Matthew. And when I read– we all have the Sermon on the Mount in our heads, but when you read it with the presence that there are certain, that there is a God, then certainly God’s celestial grandeur shines through to me in that. And in those truths about the poor in spirit, about the meek, the mercy to the merciful.

And that sermon seems to me such a moral revolution and an act of a pristine moral statement that seems to me a piece of God. And so I think the story of Exodus is a miracle. Like the fact that– people always say “do you really believe the miracles of the Bible?” I don’t know, like did Moses, or did God really split the Red Sea? I don’t know.

But the fact that there’s a book like Exodus is a miracle. And to me the fact that somebody 2000 years ago said The Sermon on the Mount is a miracle. And it is a pristine vision as close as we can come to seeing that very weird thing we call God. And so to me, I can’t unread that.

And this is going to be unsatisfying for Jews. I understand that. I can only say how I experienced God, it includes not just the Old Testament. Or not just the Torah.

Ryan Bauer: So do you–because as I understand Christianity, and I’m not an academic, is that, you know, if I look at Islam, Islam literally means submission to God. Christianity is unquestioning belief in God. And Judaism, the people of Israel, is literally wrestling with God. They’re incredibly different these three.

David Brooks: That’s well put.

Ryan Bauer: And so do you believe Jesus is God?

David Brooks: Yes, I believe he’s a piece of the godhead. I do think that God is like fire and different pieces of it come out in different ways. And but when I say faith, I wouldn’t say it’s unquestioning faith in God.

Like there’s a writer named Frederick Buechner. He says faith is change. It’s believing it one day and not believing in another. If you wake up in the morning and you ask yourself, “am I going to believe that all over again?” Then and if you say that to yourself, “yeah every 10 days out of 10, I believe there’s a God,” he says you’re lying to yourself. You should say no 5 or 7 times out of 10 because that proves you’re human. But if you can say it two days out of 10, you should say it with great laughter.

And so from–there are a lot of people I meet, more in Christianity than Judaism, who are like “yeah, I prayed to God, God told me to take the job at the law firm, but not at the medical school.” Like I don’t really resonate with that. And so, and I just want to…

I mean, there was a Muslim saying “whatever you think God is, he’s not that.” And so I want to emphasize the mysteriousness and beyond our capacity to reason. But there are people I resonate with, and Frederick Buechner was one of them, my friend Christian Wiman is another, who are wrestlers. And Wiman says “if faith was supposed to bring me peace and comfort, it’s not working for me,” and I resonate with that too.

And actually another hero of mine, Joseph Soloveitchik has a long footnote about that, where he says, in man’s search for meaning or halakhic man, one of the books, he says “faith is like going down a rocky river with craggs and valleys and rapids, and it’s not the life of the peaceful,” and that’s certainly been my experience, because once you become aware of the vertical axis–that our lives are not only lived horizontally, they’re lived vertically–then you have much more down days than you did before, when you were just living calmly on a shallow level.

But the redemption–and way before I experienced God, I experienced grace. And I felt there is an excess of love and goodness in the world that we don’t learn and that we can’t explain otherwise, except that we live in a created order and that at some foundational level there is…

We have a friend who said that when her daughter was born, she discovered she loved her more than evolution required. And I’ve always loved that phrase, because we all do some things out of evolution, but evolution doesn’t explain the love we have for each other, and it doesn’t explain Nelson Mandela. It doesn’t explain Chartres Cathedral. It doesn’t explain Ode to Joy. There’s a surplus in the universe that doesn’t need to exist, but it exists by the grace. And I feel that that is present in our reality.

Ryan Bauer: Because there’s a lot of modern Jewish intellectuals who take the you know, when you talk about the Beatitudes, of like this is morally sublime. You know Isaac Mayer Wise, Leo Beck, and countless others. That they see that, they look at the morality. They think Jesus is incredible as this historical figure.

But kind of the differentiating factor, which even, you know, in Israel in 1989 the Supreme Court–they had this case, they had this, you know, two people both to Jewish parents, but they came in and said, “we now believe Jesus is God.” And the question was posed, does that still make them Jewish? And it was kind of this defining line. I mean, even if you took most, I’d say all Jewish organizations–and Jews don’t agree on anything–if I take the Orthodox, to reformed, and everything in between, there’s one thing they would agree on, which is that Jews do not think that Jesus is God.

And the moment you kind of step over that, that’s the differentiating factor. Because one is unquestioning belief, and one is kind of wrestling, saying there’s you know more in the world that I just don’t understand.

David Brooks: Yeah no, I understand that. I would say a couple things in response. Jesus thought he was a Jew. Second, for the first 200 years the dividing line was very narrow.

We are the inheritors of 1800 years of Christian anti-Semitism that was based on very much pushing the Jews away and the Jews reacted by pushing the Christians away. And so we are inheritors of this historical tradition, erecting to me, maybe a brighter line than there should be. Final thing to say is, when you experience faith, it’s not like choosing Republican versus Democrat. It’s not something you control all the time. And it enters me as a very emotional experience.

And so my emotional tie to Judaism is through the faith of my fathers and through the peoplehood stretching back centuries and centuries.

My emotional tie of Christianity is often through Christians. And I grew up with them when I was a kid. I knew them at summer camp. I’ve experienced them recently, who are living life in a pattern that I very much admire.

And so when I was

a kid, I knew a guy named Wes Womenhorst who went to this camp I went to, and he just radiated joy all the time. And if something bad would happen he would laugh. He was the best passer on the basketball court I ever saw. Selfless even in basketball. And he went on to become an Episcopal priest and he worked with women who were suffering from domestic violence and he went down to Honduras six months a year and worked in real poverty there. His life was a gift of Agape, of selfless love.

And now we’ve soured a little on Pope Francis, but when he came onto the scene his life too seemed to be that radical conversion that frankly Christianity supposed to be. Rejecting the ways of the world and reaching to the bottom and seeing the poor as closer to God. And that just strikes me as beautiful and it strikes me as somehow true.

And you know, I’m having trouble articulating, because you go with where your heart and your soul seem to lead you, and that’s where it seems to lead me. And I realize for a lot of Jews it’s over a line. And what I say in the book is “I feel more Jewish than ever. If Jews want to get rid of me, they’re going to have to kick me out because I don’t want to leave.”

Ryan Bauer: What role–because you talk about this–what role did your wife Anne have in kind of this step you’ve taken in the past few years?

David Brooks: Well, we worked on a book together. We worked on “The Road to Character,” and she specifically worked on two chapters, mostly one, and a bit on the other. Dorothy Day, who’s this great heroine of mine, and then on St. Augustine. And we would exchange emails.

And I was just curious, like what happened to Dorothy Day was she was sort of a loose writer and poet, Bohemian in the village in the 1920s. And then in the 20s she had her daughter. And when her daughter was born she wrote–she realized while she was pregnant that all the accounts of childbirth she had ever read were written by men. And so she decided, I’m going to write one. And she gets to the–40 minutes after the birth of her daughter she writes an essay. She’s sitting there in the hospital and a lot of it is about the violence and the pain of it.

But at the end she says, “if I had written the greatest novel, composed the greatest symphonies, sculpted the greatest sculpture, I could not have felt the more exalted creator than I did when they placed my child in my arms. I was flooded by such a vast flood of love and joy, I needed someone to worship and to adore.”

And she experienced grace at that moment, and she became a Catholic. And she spent the next 60 years of her life not only serving the poor, but embracing a life of poverty and living amongst the poor in homeless shelters and communes. And she’s a wonderful example of faith in action. And you couldn’t have led her life and done the sacrifices she gave if you didn’t think that your job is to purify your soul and and to love God. Maybe you could, that’s an exaggeration, but that’s what motivated her.

And I just wanted to understand, what was somebody like that? And the biggest hurdle for me growing up in our culture was that to me life is about agency. You take control. You take control of your life. You work hard, input leads to output. But for Dorothy Day, you surrender. There’s an inverse logic to a life like that, which is you have to lose yourself to find yourself. You have to surrender to gain power.

So we exchanged these memos–a lot of them were about agency and grace. And so it was just part of the process of learning about what this thing of faith was.

And then there was a whole set of other people I consulted. You know, people from all around the country having emails and exchanges, conversations, men’s retreat.

And so there was just this long process of exploration. At the same time, emotionally and spiritually I was opening up. And so it was, I want to say, I would love to say that, you know, one day I was writing in my study and then God walked in, shined a blue light, turned my water into wine. It was all set. But it was nothing like that at all. There was no moment.

And I wanted to write the chapter to show that coming to Faith, whether it’s Jewish or Christian or Muslim, can be done by very spiritually average person in a very incremental way. And that it’s not dramatic and it’s not even that convicted some of the time. But it is…You’re just drawn by…I’m you know, maybe this is not a rigorous and rational way to do it, but I’m drawn by what I see.

And so Dorothy Day, for example, she really lived a beautiful hard life. Really, you know, living with a lot of people with mental illness. And the end of her life Robert Coles who teaches up at Harvard asked her, “did you ever think of writing your memoir?” Because she wrote an early book, a very beautiful book, called “The Long Loneliness,” early in her life. But at the end of her life, it would have been natural for her to write a memoir.

And she said “no I tried. And I took out a piece of paper, and I wrote at the top, ‘a life remembered.’ And so I sat there and how do I tell my life?” And she said, “I sat there and I thought of the Lord and his visit to us all those centuries ago and I was just grateful to have had him on my mind all that time.” And it’s very attractive simplicity and serenity to that, which I’ve never come close to experiencing.

Ryan Bauer: Because in your writing, the thing that kept coming in my mind is when you say you’re this Wandering Jew, I kept thinking he’s wandering into the 17th century with the Hasids. You know the Hasids, they had this language if they you know, their highest ideal was that they would go into a town, and if people had a whole heart, it wasn’t working. They wanted to break people’s hearts, because if your hearts are broken then the light can come in and then the light can go out.

David Brooks: I know I’m somewhat drawn to the Hasids, and to that, because they–frankly I grew up in conservative American Judaism. And peoplehood was strong. And there’s a Hasid, there’s a loving kindness that is very strong.

But at the services you don’t see what you actually see in the Hasidic tradition, which is emotional flowering. And if I want the disease, I want the pure disease. Now there are a lot of things about the Hasidic lifestyle I would not embrace, especially as I observe it in real life. But they’re charismatic and I have a lot of sympathy for the way they practice their faith. And about a year ago one of my students who’s an orthodox Jew got married.

And so we’re at his wedding. And the part I don’t like is the men are dancing with the men and women are dancing with the women, but the joy as we circled him, there are hundreds of men circling him, and he’s in the middle of the white-hot center of this convulsive collective effervescence of dancing men and he’s pulling men into the center to dance with him. And you see everyone’s swept up in this moment. And you see these 70 year old guys, it’s like they’re going to a punk rock concert, they’re bouncing up and down. And there’s just a union and a community in that that is very powerful.

And my general line is that most church services are more spiritual than most synagogue services, but most Friday night shabbat meals are more spiritual than most church services. That there’s something about sitting at a table, a Shabbat table with all the ritual with the Challah, and there’re 18 people around the table, all of them are talking at once, and they’re all correcting the other wrong things that people said. And, but there’s a sense of deep union.

And so, you know, you get drawn to that pretty–I get drawn to a lot of things. And you follow, you follow your inspiration, your aspiration of what–it’s really to me very aesthetic. It’s what’s morally beautiful, what’s morally joyous.

And part of the book is saying, you know, we shoot for happiness, and happiness is when you win a victory, but joy is better. Happiness is when the self expands and we win a victory, we get a promotion. Joy is when the self is transcended. When you feel merged with another person–a mother and a daughter. You feel merged with, you’re out in nature, you feel at one with nature. You feel merged with something that seems ancient.

And one of the stories I tell–I keep mentioning this guy Christian Wiman. He’s a poet and he was out in Prague and he was working at his kitchen table and a falcon came and landed on the windowsill. And the falcon was beautiful, he was transfixed by it, the window was down. He called his girlfriend and she came out of the shower dripping wet and they stared at the falcon.

And then the falcon turned and locked eyes with Wiman, and Wiman felt something inside just falling through him. And he felt he was looking through the centuries into this bird’s eyes, connecting with something primitive and primeval, and his girlfriend said “make a wish.” She understood the moment.

And he said–he wrote a poem later about the moment, and he said “I wished and I wished and I wished that the moment would never vanish, and just like that it did.” And faith is sometimes a little like that.

And Wiman says “faith is having some moments and then trying to stay faithful to those moments when you don’t have them.” And I’ve just come to believe that life is more enchanted than I ever knew when I was on my first mountain. That there’s magic.

That when I’m with my wife and we were around a conference room, and there were 15 people around the room and I looked at them and I said “well all these people seem nice. They all have two arms and two legs and faces and heads. But why does the room only revolve around her? Why are the mystic chords only connected to her?” And there’s something magical about that. And there’s magic in the world. And I can’t put it any better than that because I’m not a great theologian or poet. But I’ve come to believe there’s magic.

Ryan Bauer: Well, I’m going to invite you to services at Emanu-el. Because they are spiritually uplifting.

David Brooks: Oh really, okay.

Ryan Bauer: You know, I question it, because one of the things I notice is that even when you’re talking here, you’re an avid reader and you’re pulling from all over the place, and you kind of act like this bridge.

I even think back when you know, when you left University of Chicago as this Marxist, you went to the conservative paper and you acted as a bridge there. You go to the New York Times as the conservative columnist among liberal readers. You’re in your first marriage, you married a woman who converts to Judaism and eventually becomes a rabbi and then you start hanging out with…

David Brooks: She became a Mikvah lady, but not a rabbi.

Ryan Bauer: Oh sorry, a Mikvah lady. But as you go through this, do you think of yourself as a bridge? That you bridge these two worlds a lot of the time for people? That you almost translate?

David Brooks: Yeah, maybe you know…

Ryan Bauer: They like to call you the liberal conservative.

David Brooks: Yeah no, my joke about being conservative columnist at the Times, it’s like being the chief Rabbi in Mecca. Not a lot of company there.

Yeah, I’ve become impatient with myself about that actually. We have a friend who’s a painter, Makoto Fujimura, and he grew up half in Japan and half in the US. And he calls himself a border stalker. He’s sort of in between the two. And I’ve weirdly a lot of times in my life for whatever reason, have found myself in that.

A little more academic than journalists, but I’m more journalistic than academic. I’m weird. This weird religious bisexuality thing. I’m sort of a very liberal conservative or maybe a conservative liberal. And so I sometimes say make up your damn mind. And I don’t know if that’s something temperamental in me.

But there’s a concept called “the edge of inside.” That if you’re in an organization or a movement or a community, there’s some people who are at the white-hot center of it, but then there’s some people who are almost near the border, but just on the edge inside.

And he says, this guy Richard Rohr says, that’s sometimes a very creative place to be. Because you’re part of something, but you’re also looking at the outside and you’re at that verge where the two meet. And for whatever reason I tend to have that personality type, I guess, I don’t know.

Ryan Bauer: Cause being a bridge, it’s a liminal space. I think about the Golden Gate Bridge. It’s not in San Francisco and it’s not in Marin, it’s kind of in-between spaces, but not rooted.

David Brooks: You know today, I mean these days I find myself, we live in such a tribal political era, I find myself weirdly politically homeless. Because there’s nothing about the Republican party that I recognize as conservative. And I’m not a supporter of the Green New Deal. And the people I tend to hang out with tend to be Democrats because I live in big cities. But there’s frustration in that. In being liminal all the time.

Ryan Bauer: So we’re going to raise the house lights up to get some questions from the audience. And just a reminder, questions, they end with a question mark. Not with a period.

City Arts & Lectures: This question is coming from the center of the balcony.

Audience Member 1: Thank you very much for your talk and your book. You mentioned that Abraham Lincoln was trying to unify the country after the Civil War. He challenged people to a radical turning of the heart to do that. Today we have people who are earning billions of dollars, organizations and people, to divide our country and keep it divided. And I wonder if you have any insight, since it’s really about all of us as people and individuals, what we can do? What we can do as individuals and as a country to unify?

David Brooks: Yeah, so I wear this little pin, which I should explain now. I decided we were becoming too fragmented, too divided along class lines, along racial lines, along social lines, along political lines. And social isolation was the core problem and fragmentation, but it’s being solved at the local level.

And this, my organization is called Weave: The Social Fabric Project. And the people who are saving the country are people we call Weavers. And there are millions of them around the country. There are probably hundreds in this audience. And basically they are people who cross divides, who build relationships.

And so in Chicago we ran into a woman named Aisha Butler who was living in Englewood, which is a tough neighborhood in Chicago. She was going to move out because she had a nine-year-old daughter, she was afraid for her safety. And as she was moving out, she saw two little girls in the lot across the street playing with broken bottles. And she turned to her husband and she said, “we’re not leaving that. We’re not going to be just another family who left that.”

So she Googled “volunteer in Englewood” and one thing led to another, and now she runs the big community organization there weaving the fabric of Englewood together. And these people are everywhere. Some of them have had horrible valleys.

There’s a woman named Sarah Atkins I met in Ohio. She came home with her mom on a Sunday evening, from a day of antiquing, and found that her husband had killed their kids and himself. And she now serves with women who’ve suffered violence. She’s a pharmacist and teaches pharmacy. She has a free pharmacy. She lives a life of selfless giving. And she’s told me, “I did it because I was angry. Whatever he tried to do to me, screw you, you’re not going to do it. I’m going to make a difference in this world.”

And so we just run into hundreds of these people. And in my view–some of them run big organizations. Some of them just do what people used to do naturally. Ran into a woman in Florida who was helping kids leave an Elementary School across the street and she was asked “do you have any time to volunteer?” And she said “no, I have no time to volunteer.” And she was asked, “what are you doing this afternoon?” “Well on Thursdays I take food to the hospital for the ill.” And, but you don’t volunteer, and she said “no, I have no time to volunteer.” She didn’t consider it volunteering. She considered it neighbor. That’s what neighbors do.

And so in my view there are millions of these people who are a movement that doesn’t know it’s a movement. And society changes when a small group of people find a better way to live and the rest of us copy them. And these Weavers have found a better way to live. And they live for other, not for self. They live for their community. They’re planted in their community and they just want to live good lives and be in right relationship with others.

And so my view–history changes when there are social movements. And social movements will lead to a knitting together the fabric of our society, a shift in behavior and a shift in norms, and then structural changes to fix things like the tremendous gap between rich and poor.

And I’ve had a depressing political year with Washington. I’ve had an amazingly inspiring year traveling around the country being with these Weavers. And you know, I’m just totally convinced that what they do doesn’t scale, because it’s about relationship and it’s one-on-one, but norms scale. And if you can shift the norms of society, you can just have a gigantic effect. And that’s my hope for the future.

City Arts & Lectures: This question is at the center of the orchestra.

Audience Member 2: Thank you. You talk a lot about, or at the beginning talked about hyper-individualism as the ill in our society today and the need to look to moral traditions that have a sense of community. And at the same time you have a sense of pulling things from all of these different communities and creating really an individual philosophy that’s very inspirational and meaningful. And I’m interested in how you square those two thoughts.

David Brooks: Well my philosophy is relationalism. It’s that life is not an individual journey, that you can’t be happy on your own, that career success does not lead to fulfillment, believe me, I’m an expert on that. But if you understand that the motivations of your ego–can I be better than others, will people see me, how do I rank, what’s my reputation?–if you realize those are very insufficient motivations and that you’ve got deeper motivations coming out of your heart and soul and you’re morally transformed, so when you’re broken open, you really try to live out of your heart and soul and put relationship first. And that our society will be rewoven as we learn to do that.

And not only say it. It’s easy to say I’m putting relationship first. It’s actually very hard to be a good neighbor. It’s actually very hard to put neighborliness above privacy. It’s actually hard to be a good husband and wife. To do relationship well is a skill. And so I would say that’s my philosophy.

And another phrase for it, it’s a historical tradition. The phrase for it is personalism in the 19th century. And Gandhi drew on this and Martin Luther King drew on this. Dorothy Day drew on this. And it’s a belief that the egotistical desires of self-interest which Thomas Hobbes and John Locke and every economist under the sun say is at the center of the human person–it’s a belief that that’s wrong. That human beings are capable of living their lives as gifts.

And the reason those people thought, Thomas Hobbes thought self-interest and the desire for power was at the center of the human experience, is because he lived in a society of alpha men who did not even see the systems of care that were being built around him by women. And so I, that would be my philosophy. And it’s part of a historical tradition that I think is, we live it out, but we don’t have the name for that philosophy.

City Arts & Lectures: This question is coming from the balcony towards your right.

Audience Member 3: So I’m a local high school teacher and we were talking today in class and I showed your clip from the NewsHour to a hundred and fifty high school students of the–when you talked about the book just last week on the NewsHour. And one of the students asked me a question and I said, “well, I’m going to go see him tonight, so I’ll ask the question.”

Ryan Bauer: This is going to be the hardest question of the night.

Audience Member 3: It comes from a high school student. So the question was, “do you think that President Trump acts the way he does because he’s lonely?”

David Brooks: Very good question. I hasten to psychoanalyze the guy cause I don’t know him. But I am a pundit.

My interpretation is that somewhere he wasn’t loved. And out of that pain, he became unlovable. He closed himself. He is a person who I think can’t love and can’t be loved. And that’s because he’s reduced himself to a parody of the first mountain culture. Where it’s all about financial success, it’s all about performance, it’s all about ego. And he to me is a perfect exemplification of how pride is self-torturing. And that when you base your life on pride, you’re fragile, because the world is never treating you as well as you think the world should be treating you. And if you care about money, you’ll always feel poor because you’ll never have enough. As soon as you achieve anything your desires leap out ahead of you and you’re always dissatisfied.

And so I think he’s a man friendless, used to combat, and I find him more lonely. I, believe me, I have contempt for a lot of the things he does, but there’s an element of pity, I would say. Because I don’t think even in his close relationships, and the people in the White House–one of them said to us a year or two ago, “in past administrations, was there a sense of camaraderie?”

And every past administration I’ve ever covered there’s an awesome sense of camaraderie. They feel they’re going to battle together and they’re going to do some good together. But in this White House, it’s a snake pit as far as I can tell. And the culture of the place comes from the top. And so it’s a man incapable of real relationship. And whatever happened in his childhood that caused that, or biological I don’t know, but it seems that wound is at the core of a lot of what we see.

Audience Member 4: Hey, so, um, I was in prison for 7 years and I got out last year. I remember four years ago, when I was 22, I was, the books were my best friends. And I remember uh, sleeping hugging a book, you know Plato, the Bible, I read a lot of times. And I remember those being one of the best moments of my life.

So I got out last year and I couldn’t help but to feel the social pressure to have material things. I look at my friends that have degrees, houses, wives, kids. And I didn’t even have a girlfriend. So I felt the pressure. So the more I’m like ,you could say manifesting, the more I’m you know, abiding by the physical world, my spirit, my soul is like “my friend, why have you neglected me?” So my soul has an Italian accent for some reason.

So I listened to you this morning on NPR and you spoke about good people. How good people should not be determined from what materialistic things they have, and I thought to myself I was like, “wow, I would like to ask this guy, what does he think of my dilemma?” So here I am. Asking you, what do you think about this? The neglect of my spirit without, you know, while living in the physical world where economy, you know social norms are a thing?

David Brooks: Thank you for that. You’re a remarkable young man. You’re living a very kick-ass life as far as I could see. You know, one of the things that’s in the book is that I have a chapter on people who’ve experienced this state of transcendence way more powerfully than I ever did, and I focus on people who are in prison. And so Nelson Mandela, Václav Havel, Doestoevsky, Anwar Sadat.

A lot of people have had very profound spiritual experiences while in prison and that’s because basically a lot else has been taken away. And a lot of the material things have been taken away and they have their inner life. And it becomes his very life altering experience. Viktor Frankl’s another one. And they taste the highest sensibility when everything else has been taken away.

But then of course you get out in the world and the lures of the world are there. And I’m not against enjoying a good glass of cognac or whatever, or having a nice car or a nice house. I think the wisest way to walk through the world is in the world, but also–and embracing the meritocracy and all the stuff that goes with achievement–but always having with you a different and competing moral system.

And so the Puritans had a sense that we have two callings. And that we have a calling to improve the world physically and be involved in the world. But then also a calling to serve almighty. And those two sometimes compete and they should correct the other.

And Judaism very much has–you can say better than I– but it’s a worldly religion. We are here on this Earth and this Earth, it’s not like just a motel we’re passing through. And so achievement on this Earth is very important. The things you do on this Earth are very important. But having a competing value system seems to me essential or else you get totally sucked into the value system of the meritocracy.

And so having the job you do by day, but seeing it through a moral lens. So the book is really about not just having a career, but having a calling. And the difference is that a career is something where you try to use your skills and to get the most you can, most money you can. But a calling, you’re summoned. There’s a problem in the world and you think wow, it’s my responsibility to solve that.

And so Viktor Frankl, this guy he was a psychiatrist in the 30s, and he asked himself early in life, “what do I want from my life?” And the Nazis invaded and he was sent to Auschwitz. And in the prison camp he realized, what do I want from life is the wrong question. The right question is what does life ask of me? And what’s my responsibility here? And he was a psychiatrist in a prison camp, so he made a study of suffering.

And so your life experience has probably helped you address a problem, which is in our society, which is there are a lot of young men who need credible messengers to tell them how to live. And because of your life experience, you’re a credible messenger.

And so when we select are calling, it should be something our past life has uniquely prepared us for. And it should be something we find beautiful. And if you can find beauty in say, being with young men who may be adrift, then maybe that’s the problem for you.

But somewhere out there there’s a problem that your life and your inquisitive spiritual mind has prepared you for, and it’ll come. Life has a way of helping us out and the problem lands in front of you and you think yeah, that’s my problem. But seeking problems is one way to find a calling.

The other final bit of thought that comes into my head is from Nietzche. He said one way to find your calling is to take the four most beautiful moments of your life, write them down, and see if you can draw a thematic line through. And if you can do that and there’s a line through them than you’ve found the law of your very life and you can head in that direction. That’s what I got. But good luck to you man. You’re gonna, you’re gonna kill it.

Ryan Bauer: And with that David I want to thank you for sharing your soul with us tonight.

David Brooks: Where am I looking?

Ryan Bauer: You’re looking at right over here, right next you.

David Brooks: That doesn’t help me. Oh, right over there.

Ryan Bauer: David, to the chair to the left of you.

David Brooks: I thought I was the voice of God. I was going to convert back.

Ryan Bauer: Thank you, David.

David Brooks: Thank you.